Africa Scene: An interview with Roger Smith on Cape Town corruption

Roger Smith’s thrillers are published in eight languages and two are in development as movies in the U.S. His books have won the German Crime Fiction Award and been nominated for Spinetingler magazine’s Best Novel awards.

As compelling as ever, SACRIFICES is knotted like a noose that starts to tighten from the very first page. Wealth insulates Michael Lane and his family from South Africa’s violent crime epidemic until his disturbed teenage son, Christopher, commits a crime that throws the delicate balance into a spin-cycle of revenge and retribution that threatens to destroy Michael Lane and everything he loves.

I’m curious to know why SACRIFICES has only been published in South Africa two years after it was first released.

SACRIFICES was released digitally in July 2013, but 2015 is really its year. It was published in France and Germany early this year and most recently in South Africa. The reviews in France have been great. Le Monde called it “Crime and Punishment in South Africa,” which tickled me no end, and it made the KrimiZeit 10 Best for July, chosen by 21 critics from Germany, Austria and Switzerland, in the company of Don Winslow and James Ellroy.

Congratulations! Good company indeed! Now to the novel. Wealth and poverty are again in the spotlight–but there’s more to it. A general and pervasive lack of humanity seems to exist in this novel. Do you agree?

Yes. The characters in the book, like most South Africans, are numbed by crime which has eroded their empathy and humanity and makes them capable of acts of extraordinary callousness and brutality.

And again, intimate crimes in intimate settings–particularly the insular nuclear family imploding –is a theme that you’ve explored in SACRIFICES. Can you comment on this?

When I set out to write SACRIFICES, I made a conscious decision to limit the point of view characters to two: Michael Lane and Louise Solomons. In my previous books, I wrote four or five POV characters per novel, to create quite a broad, sweeping canvas, where the city (and the country) was as much a character as the people were. I wanted SACRIFICES to be a more contained, claustrophobic book. I wanted the reader to be enveloped in the worlds of Michael and Louise. Also, SACRIFICES is, more than any of my earlier books (although Capture gives a hint of where I would go next) a psychological thriller, and the inner lives of Michael and Louise are as important as their actions.

I suppose the meltdown of the nuclear family is a metaphor for South Africa’s troubled society with its corruption, brutality, and loss of moral center. In SACRIFICES I wanted to show how an attractive, privileged, white, liberal, English speaking family like the Laneswho, ironically, have erected walls around their Cape Town mansion to keep the perceived danger, darkness, and evil out) are in fact deeply compromised and corrupt, and how they justify their corruption by saying that, well, everybody else in the bloody country is doing it, there is no law, no justice, so what the hell, why shouldn’t we do it, too? Which, I think, is a typically South African attitude.

Michael Lane, in fact, considers Crime to be South Africa’s ‘undeclared war’. He logs on at one stage, to a website called Bearing Witness where statistics and details are collated of those who’ve been murdered. I wondered if this an actual website?

Lane is referring specifically to murder. We all know the murder statistics in South Africa are tragically high, the body count resembling a war zone, hence his notion of the “undeclared war.” The website, which consists simply of a scrolling script reading out the names of murder victims, is my own invention, but I’m surprised the families of victims haven’t created something like this. It would be chilling.

Looking more closely at Michael Lane–father, husband, bookstore owner–one might say that he too is a victim of circumstance and manipulation. He’s a weak man never able to face his past, or take responsibility for his actions. Is Michael Lane, the epitome of white hypocrisy and white guilt, included as part of the metaphor you talk of earlier? He weeps, at one stage, with “the knowledge of all he has done, and all that has been done to him.” He can’t face what he’s done, yet he can’t come clean.

Michael Lane isn’t just white, he’s English speaking, which for me is very telling distinction. Culturally, he has always felt an affinity with the UK and the U.S., which has enabled him to be simultaneously South African and part of the hugely dominant global culture the English language carries in its wake. Michael, in a moment of absolute truth, would consider himself (because of his Englishness) to be superior to other South Africans, to be somehow exempt from what he perceives as their brutality and lack of sophistication. So, yes, he carries personal guilt for what he has done, but he also—like many English white South Africans (and I would include myself in this group)—found it easy to point fingers at the Afrikaner for the ills of apartheid, and finds it easy, now, to blame black South Africa for the current mess, while keeping himself at a remove. And, of course, that detachment is part of his failure as a human being, a failure that allows him to absolve himself of his sins of commission and omission.

The other central character, Louise Solomons, the daughter of the Lane’s live-in domestic worker, as you mentioned, plays a parallel role. Is she then representative of, or a manifestation of, anger and neglect of the oppressed?

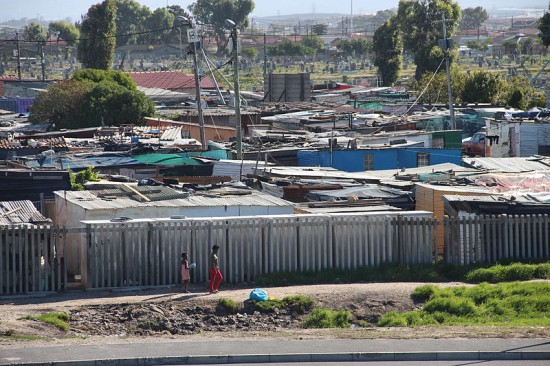

I think Louise is one of the most tragic characters I have written. I know that the physical circumstances of some of the people in my other books (who face extreme poverty, sexual abuse, and relentless brutality) were harsher, but Louise finds herself in a very alienated place, caught in a very South African psychological trap. As a child she benefited from the patronage of the Lanes, the wealthy people who employed her mother as a domestic worker and housed her family in a small cottage on their property, and so she was drawn into their orbit. She was sent to good schools, she learned to speak English with a neutral, suburban accent, a “white” accent, very different from her mother’s. (When talking to mixed race people on the telephone she is always mistaken for being white.) As a child she believed—in a fantasy that was a product of the attention Michael paid her—that one day she would be invited to live in the mansion, would cross through the mirror and become somebody very different.

This never happened. And, although Michael funds her education at the University of Cape Town, she finds herself marooned in a no-man’s land between cultures: not part of ghetto Cape Town, nor really part of the plush white suburbs, and she hasn’t managed to find a place for herself in the small, “raceless” world of the urban sophisticate. This makes for a deep rage and resentment, which finds tragic expression in the book. Her character speaks to me very vividly of the calibrations of color that still exist so powerfully in South Africa, even twenty-one years after the end of Apartheid.

And it seems clear that children sadly continue to pay the price of Apartheid–certainly in your novel–as innocent victims, as the sacrificial lambs. Do children pay for the sins of the fathers?

I find it almost impossible to write about South Africa without some sense of the sins of the past informing the sins of the present, and the children picking up the tab for their fathers’ iniquities. Having said that, Lane’s son, Christopher, is no sacrificial lamb, he is a sociopathic rugger-bugger who, high on a cocktail of booze and steroids, kills a young woman in the first chapter of the book, and is the catalyst for all the devastation that follows. Chris, of course, was conceived on the night Michael Lane committed a terrible crime of his own, so who knows exactly how the karmic wheel spins?

That’s interesting, since all the time I was reading I felt that this noir thriller was more than simply a stunning plot. It’s particularly fable-like. Did you consider karmic justice when writing?

Yes, I suppose that SACRIFICES is a bit of a morality tale. Implicit in the story is the belief that the South African criminal justice system is so compromised that it can provide no remedy, so the remedy has to come from elsewhere. Karma, if you like.

Louise also suffers from the sins of her biological father, Achmat Bruinders, a convicted gangster, who gets drawn in to the final spirals of the novel. Is he then, representative of a breakdown of rule of law? “Law,” as we know it, no longer exists for any of these characters, and you mentioned earlier that South African society is largely corrupt, with “no law, no justice.” The philosophy “an eye for an eye” exists. How powerful is the informal law of the street, and the gangs, in SACRIFICES, and in SA society itself?

Achmat Bruinders is man who spent many years in prison for murder, and has developed his own idea of the law, based on the codes of the prison gangs—codes built on reprisal and vengeance. Achmat articulates this to Louise, when he explains that he will kill the child of a man who killed his son: “The law is the law, girly and the law is all we have.” This is certainly not the law in the conventional sense, but it could be argued that in South Africa today the law of the streets is more effective than the law of the police and the courts.

I’d like to ask you about another “character” in the novel, the book store which Michael Lane owns and runs. Lane’s Books plays a significant role as the safe haven to which he escapes when overwhelmed by all that is spiraling out of control around him. Do you see the bookstore as a last bastion of civilization?

Well, obviously I love books and I love bookstores, but in South Africa, where books are iniquitously expensive (priced beyond the pocket of the vast majority of South Africans) and the reading population is tiny, bookstores really are little oases of privilege, aren’t they? When people can’t afford bread, the notion of buying a book is outlandish. And, of course, Michael Lane is independently wealthy—his wife has parlayed an inheritance into a property empire—so the bookstore is a conceit, a hobby, where he can sit surrounded by his beloved tomes and live out his fantasy of himself as a man of taste and culture, insulated from the crime and carnage outside its doors.

To look at the broader context, you reference, in SACRIFICES, two particular texts, ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS, and Philip Larkin’s poem THIS BE VERSE, both of which offer understanding of the novel on a deeper level. Why choose these texts? What do they tell us about Michael and Louise?

I have always loved THIS BE VERSE in which Larkin paints a very bleak picture of the family, of how “man hands misery on to man,” which refers back to your previous question. And with Michael Lane being the bookish man he is, it worked very well for him to love Larkin, too, and share his jaundiced world view. And it’s very believable that he would, in the month of Louise’s seventh birthday, invite her into the cozy warmth of his kitchen, make her hot chocolate, and read to her from THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS.

Lane, of course, was aware of the irony of his choice of book, was aware of how he was drawing this brown child through the looking-glass into another world. Or, at least, dangling the promise of that before her. It is one of Michael Lane’s greatest failings (and he has many) that he was able to be affectionate to Louise when she was a child and could be conveniently sent back to her mother, but became incapable of continuing a meaningful relationship with her when she matured, when the demands of that relationship became greater.

Louise becomes obsessive in her need for attention from Michael, which is in keeping with the kind of emotional anxiety you develop. It struck me too that your work often introduces some sort of sexual tension. I remember a particularly powerful vignette from your novel Dust Devils–the sex-addict cop, Disaster Zondi, goes to a sex-addicts help group. It has always stayed with me, the sheer intensity of that brief chapter, the mood of sex as escape, as addiction. For Michael Lane, there seems no pleasure in sex. Is sexual dis-ease another theme that finds its way into your novels?

Booze, drugs, sex—the escape hatches of the desperate and the guilt-stricken—are always features on the landscape of my books, but Lane does take pleasure in sex. The book opens with him and his wife, Beverly, in the throes of sex and he’s still aroused by her after many years of marriage: “. . . if Lane no longer loved his wife his desire for her was as intense as it had ever been, and he marveled sometimes that lust, the thing that had ignited the love he’d once felt for her, remained now that the more tender emotion had been eroded to nothing by the years.” After they do the terrible thing that they do, Lane withdraws from his wife sexually, and this signals the end of their marriage and their unholy alliance.

I think that sums up things nicely. SACRIFICES is indeed a noose of unholy alliances, with every word tightening to the climax of the last line. What else would one expect of Roger Smith? Lastly, can you tell us a little about your foray into horror writing? Was the cross-over from writing crime a natural progression?

I think crime and horror are kissing cousins. Some of my villains (particularly the very evil Piper—the escaped convict in WAKE UP DEAD—and Bone and Tard in MAN DOWN) would be equally at home on the pages of horror novels. Writing crime fiction set in South Africa is quite rigorous—because of the recent history of the country and its very particular social ills there’s a demand for authenticity. I wrote my horror novel VILE BLOOD (as author Max Wilde) as a kind of antidote to this. It’s set in an imaginary America, and it’s a classic tale of good and evil. Which, I suppose, could sum up my crime novels, too. As I said, kissing cousins.

Thanks for the chat, Roger. I look forward to catching up next year.

*****

Joanne Hichens is an author, editor, blogger, and a teacher of creative writing. She is currently taking a break from teaching to complete a PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS). She is the author of DIVINE JUSTICE, a Rae Valentine thriller, which will be followed by SWEET PARADISE to be published in 2015. She has edited several collections of short stories, including the BED BOOK OF SHORT STORIES – a collection of writing by African women, and BAD COMPANY – a collection of south African crime-thriller fiction. She is curator of the SHORT SHARPS STORIES AWARDS, which is an initiative backed by the National Arts Festival to encourage the writing of South African fiction. The inaugural collection, BLOODY SATISFIED, a crime-fiction collection, was published 2013, followed by ADULTS ONLY – stories of love, lust, sex and sensuality, in 2014. INCREDIBLE JOURNEY will be published 2015. Joanne believes in promoting South African fiction in order to entrench a reading and writing culture.

Joanne Hichens is an author, editor, blogger, and a teacher of creative writing. She is currently taking a break from teaching to complete a PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS). She is the author of DIVINE JUSTICE, a Rae Valentine thriller, which will be followed by SWEET PARADISE to be published in 2015. She has edited several collections of short stories, including the BED BOOK OF SHORT STORIES – a collection of writing by African women, and BAD COMPANY – a collection of south African crime-thriller fiction. She is curator of the SHORT SHARPS STORIES AWARDS, which is an initiative backed by the National Arts Festival to encourage the writing of South African fiction. The inaugural collection, BLOODY SATISFIED, a crime-fiction collection, was published 2013, followed by ADULTS ONLY – stories of love, lust, sex and sensuality, in 2014. INCREDIBLE JOURNEY will be published 2015. Joanne believes in promoting South African fiction in order to entrench a reading and writing culture.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024