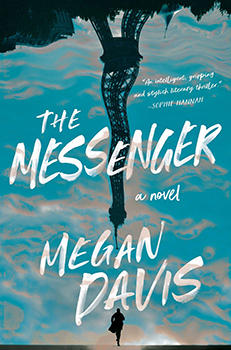

Features BookTrib Spotlight: Megan Davis

A Murder He Didn’t Commit—A Conspiracy He Couldn’t Imagine

I’m trying to piece together what my father was doing before he died—who he was seeing, what he was working on. I need to know who killed him.

I have to prove it wasn’t me or Sami.

In Megan Davis’s THE MESSENGER, a young Parisian named Alex Giraud makes the mistake of his life. Stifled at home, mocked at school, and rebellious by nature, he plans a robbery with his friend Sami, and it goes very, very wrong. The victim dies. It is his father.

But he was alive when they ran away.

Arrested anyway, convicted, and imprisoned, Alex is now out on parole seven and a half years later, and he has a single mission: to find the real killer. But he has no idea what he’s getting himself into.

Alex’s father, Eddy, was a journalist, investigating organized crime and corruption, and Alex is sure the answer must lie there, but as he talks to Eddy’s friends, colleagues, and lovers and digs into Eddy’s notebooks, the deeper Alex goes, the murkier it gets. Decades-old events suddenly become new. A terrorist incident comes out of nowhere. A suicide begins to look like murder. Alex’s email is hacked, his room is trashed, and he is beaten in the street. And the truth, when it finally comes, will be like nothing he ever expected.

Alex always knew Paris had a dark side. He always knew his father had deep secrets. He could not have imagined how deep, how dark.

“Eddy was trampling on a minefield,” one person tells him. “Things were bound to blow up.” Alex is about to be caught in the blast.

“THE MESSENGER is based on a true story I came across when I lived in Paris,” says the author. “It was a shocking case about a boy who killed his father in a dispute over the boy’s allowance. My sons were at the same school as this kid, and although they were a lot younger than him, it was the first time a really gruesome and tragic story had entered my orbit.

“In retrospect, I was feeling guilty about uprooting my kids from their friends in London and putting them into a school where they had neither friends nor the ability to make any since they didn’t speak the language. They were both miserable and hated it! I guess in that context I took a keener than usual interest in the patricide case, and I started wondering what it took for a child to really hate a parent so much that they’d want to kill them. Perhaps I was worried that my kids would grow up wanting to kill me for this French experiment I was imposing on them.”

The book grew to become much more than a question of patricide. The more Davis discovered about Paris, the more she realized how contradictory the city was.

“THE MESSENGER took a long time to write, with a few false starts and several abandonments along the way while I developed the plot.

“I was living in Paris when I started writing it, and I did a lot of exploration of the city and its suburbs. Paris is the kind of city you can really enjoy wandering and getting lost in because you’ll always come across something unusual and thought-provoking. I realized quickly there were two very different sides to the city. There’s the beautiful historical center with the Eiffel Tower, the luxury boutiques, restaurants, and all the monuments—that’s the Paris everyone knows and loves. Then there’s the grittier underbelly—the high-rise projects in the suburbs where most of the population live.

We tend to think of media misinformation being something associated with the digital age, and of course, digitization means that misinformation spreads so much more widely these days, but it was rife during the Cold War, too.“I started writing THE MESSENGER around the time of the November 2015 terrorist attacks. After the attacks, a state of emergency was declared in France that lasted for two years, during which time this schism between the two Parises became very marked. The ring road around the center of Paris, the Boulevard Périphérique, became like a barricade that separated the center from the suburbs.

“Everyone lives in small apartments in really close proximity to each other, so a lot of social life takes place on the street and in terrace bars and cafés. The convergence of so much activity between different groups also contributes to a lot of tension. The breakdown in the relationship in the story I was researching for THE MESSENGER seemed to reflect this aspect of Paris. The tension in the relationship between the father and son seemed to tie in with this clash that was going on between the older, vested interests of the central tourist zone, and the newer immigrant communities in the suburbs.”

Davis also discovered the ancient forts near that ring road—buildings that would play an important part in her story (I won’t give it away): “These forts do all exist. Some have been bulldozed and developed into large project-style apartment blocks. I was careful to be accurate about the names and location of the forts, particularly those of the inner ring, which lie just beyond the boulevard Périphérique. There are two ‘rings’ of forts and other defensive structures built in the nineteenth century to protect Paris from external attack, in particular from the Prussians who came right up to these defenses in the 1871 Siege of Paris and bombed Paris from the edge of the city.

“Each of the forts has a fascinating and often terrible more recent history, some of which is linked to French collaboration in WWII. This is a topic that is not widely discussed in France, so the forts have this sense of secrecy and mystery, and many are largely forgotten or ignored. Some of the forts are still owned by the Ministry of Defense and retain a quasi-military purpose housing key parts of the French security infrastructure, such as the black ops division of the French secret service and various divisions of the military and the police.”

Also not widely discussed in France: some of the country’s seamier history during the Cold War: “Part of the inspiration for Eddy and the other journalists in THE MESSENGER comes from the Mitrokhin Archive which was a cache of top-level KGB documents smuggled out of Russia in 1992 by Vasili Mitrokhin, a KGB archivist.

“The official historian of the UK security service MI5, Christopher Andrew, together with Vasili Mitrokhin, compiled two volumes based on material in the Mitrokhin Archive. These provide details of the Soviet Union’s secret intelligence operations around the world, including post-World War II infiltration of the West.

“I looked into the Soviet Union’s activities (known as ‘active measures’) in France, which was only a small (but fascinating) part of the Soviet Union’s worldwide activities. According to the Mitrokhin Archive, a number of high-profile French journalists were Russian ‘agents of influence,’ and several publications were set up in France to disseminate pro-Russian propaganda and misinformation.

“We tend to think of media misinformation being something associated with the digital age, and of course, digitization means that misinformation spreads so much more widely these days, but it was rife during the Cold War, too.”

Put all this together, and it’s no surprise that many of Davis’s influences are spy novelists. “I really enjoy Cold War espionage stories—John le Carré and Ian Fleming, of course, and moving beyond the Cold War to the depiction of dysfunctional spies in the fabulous novels of Mick Herron. Going back to when I was much younger, I enjoyed writers like James Clavell, Len Deighton, and Leon Uris. I recently re-read The Day of the Jackal by Frederick Forsyth and absolutely loved it. Those authors all wrote about what they knew. Many of them had ‘seen action’ in one way or another, and the authenticity really comes across. I also adore Patricia Highsmith and Peter Swanson for their quick-witted noir style. I love real-life stories of rogues, con artists, and financial crime.”

One real-life story she didn’t appreciate was one very close to her—and another motivating factor for much of what is in THE MESSENGER:

“I was a whistleblower when I worked as a lawyer in the financial services sector. My employers offered me the opportunity to engage in a massive fraud, but I not-so-politely declined their offer and blew the whistle instead. There was a lot at stake, and I was pursued relentlessly and sometimes frighteningly in my home and threatened on the street with my children: they were making it clear to me that they knew where I lived. Through this experience, I saw what people are capable of when their scams risk being exposed. I witnessed the lengths greedy people are prepared to go to for money. It was the most frightening experience I’ve ever had.

“I really admire investigative journalists who expose fraud and corruption. They often go through similar kinds of victimization and are regularly subject to physical and legal threats just for doing their job. In THE MESSENGER, several of the characters are investigative journalists, and I wanted to explore that world and the risks involved in exposing the truth. In a strange way, it is easier than ever to call out wrongdoing now, but it seems to be getting much more dangerous as well, and journalists are at the front line.”

There are a lot of cross-currents surging through THE MESSENGER—and they all come together to great effect. Next up for the author is a thriller set in the south of France called Bay of Thieves, which follows a group of people who service the wealthy elite living between London and Monaco and “explores the seductive yet distorting power of wealth, and also gambling.”

One thing that’s not a gamble: the audacity of THE MESSENGER.

Neil Nyren is the former EVP, associate publisher, and editor in chief of G.P. Putnam’s Sons and the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among the writers of crime and suspense he has edited are Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler, John Sandford, C. J. Box, Robert Crais, Carl Hiaasen, Daniel Silva, Jack Higgins, Frederick Forsyth, Ken Follett, Jonathan Kellerman, Ed McBain, and Ace Atkins. He now writes about crime fiction and publishing for CrimeReads, BookTrib, The Big Thrill, and The Third Degree, among others, and is a contributing writer to the Anthony/Agatha/Macavity-winning How to Write a Mystery.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet.

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024