Features Reed Farrel Coleman

Coney Island, Pizza, and a Trip Down Memory Lane

Reed Farrel Coleman was a mere lad of 15 when he stumbled across his first dead body. He was on his way to work at Baskin-Robbins (my dream job, by the way) when suddenly the usual mid-day sounds of those mean Brooklyn streets were shattered by the unmistakable sound of a gunshot.

I know this because today, Coleman, who’s written over thirty novels, won the Shamus four times, as well as the Scribe, Audie, Barry, Macavity, and Anthony Awards, and has been nominated for an Edgar four times, is at the wheel of his bright red SUV, pointing out the exact spot to his passengers, of which I am one. The other two, crime writer and ex-cop David Swinson and novelist and short story writer, Christina Chiu, are guests on what I like to call the Reed Farrel Coleman Coney Island Pizza Tour. When you combine pizza with witty, fascinating, intelligent (usually) conversation, I’ll happily jump on the pizza wagon.

And so, on this sunny morning in mid-May, Christina and I hop the train out to Coney Island from Manhattan, where we’ll rendezvous with Coleman, driving in from Long Island where he lives with his wife, Rosanne, and David, coming from Queens.

I met Reed for the first time when we shared the stage for a bookstore panel promoting Akashic’s Long Island Noir, to which Reed and I contributed. We became friends and now this is my fifth or sixth time on the tour, having been accompanied in the past by crime writers Lee Child, Matt Goldman, Michael Wiley, and Tom Straw.

Pizza isn’t the only thing on the menu today. For no extra charge, Coleman throws in a trip down Memory Lane, which includes a tour of his old neighborhood haunts, along with a special bonus, following the path of the famous subway-car chase in William Friedkin’s The French Connection.

We rendezvous at Stillwell Avenue, across the street from the original Nathan’s. As soon as Reed pulls up, we hop in, me in front, David and Christina in back and we head to our first destination, Totonno’s (my personal favorite).

We’re disappointed to find that restaurant is closed, forcing Reed to recalculate. On the way to Spumoni Gardens, we approach the spot of that shooting, and Reed describes the scene.

“The guy picked up the company payroll at the bank and was heading back to the Ford dealership where he worked. I was young and stupid, so instead of running away from the shot, I ran toward it,” he says. There, in the middle of the street, a man lay dying in a pool of blood, surrounded by onlookers. Reed watched as the attendants rushed to the fatally wounded man. He watched as one of the attendants removed one of the victim’s shoes and, with a pen, slowly moved it back and forth on the sole of his foot. Later, Reed learned he was looking for what’s called the Babinski reflex, an automatic movement upon the stroking of the sole with a blunt object.

The tour continues and the next item on the agenda is William Friedkin’s class car/subway chase scene in “The French Connection,” filmed under what used to be the B train. Reed points out the building where an assassin takes a shot at Gene Hackman’s character, “Popeye” Doyle, and regales us with some French Connection trivia, like the whole scene being shot without formal city permission.

I realized I didn’t want to be a Robert B. Parker imitator because no matter how good I was at it I would never be him nor would my work be seen as anything but quality pastiche.Finally, we reach Spumoni Gardens, where Reed instructs us to order “the square,” which resembles Sicilian pizza, but with the sauce on top of the cheese. Once our pizza wedges sleep with the fishes, we pile back into the car and embark upon a nostalgic ride through the streets of Brooklyn.

Reed slows down in front of a series of red-bricked apartment houses. This, he explains, is where he grew up with his two older brothers, Jules and David. When asked for the name of the ’hood, Reed explains, “If you want to stretch it, I could have been considered to have grown up in four neighborhoods: Brighton Beach, Coney Island, Sheepshead Bay, Gravesend. In some ways, I think growing up on the border of all these neighborhoods shaped me because I didn’t actually belong to any one place. When I was a kid, I would say I was from either Brighton Beach or Sheepshead Bay. What I discovered once I began touring [to sell books] was that it was easier to say I was from Coney Island because people from outside New York had heard of Coney Island. I also have more of an emotional attachment to Coney Island than to those other places. I lived at 69 Manhattan Court, a four-and-a-half-room apartment above a boiler room and in front of the block’s dumpster, from the time I was two until I moved out permanently when I was 21. My parents stayed there a few years longer.”

Coleman attended Lincoln High School, which boasts a Who’s Who roster of alums like Arthur Miller, Joseph Heller, Neil Diamond, Neil Sedaka, Harvey Keitel, Louis Gossett, Jr., Leona Helmsley, Buddy Rich, and athletes like Stephon Marbury, Sebastian Telfair, and NY Met star Lee Mazzilli.

The conversation soon turns to Reed’s work history.

“I drove an oil truck on Long Island (where he and his wife now live) on and off for seven years. I also worked the cargo area at JFK for five years, and that was only a few years after the Lufthansa heist [the heist at the center of Martin Scorsese’s award-winning film, Goodfellas]. Between those two jobs, I leased cars, bartended, cooked, waited tables, opened restaurants, and did some other assorted jobs.

“At my first job at JFK, I worked with a warehouse manager who carried an Ivory-handled .45 and when he got really upset at things, he’d fire the office shotgun at the corrugated steel bay doors and send us scrambling for cover. And any box that was delivered damaged got pilfered because we knew the shipper would put in an insurance claim. The saying went, ‘If it fell off the truck on Tuesday, we were wearing it or selling it on Wednesday.’”

Coleman has been called “a hard-boiled poet,” which alludes to his first love.

“I began writing poetry when I was 12 and was published when I was in high school. I am perhaps the only person ever to quit the football team to become editor of a literary magazine. At Brooklyn College, I studied with David Lehman, and Allen Ginsberg read out of my Norton Anthology when he visited our class. I was just too cool to ask him to sign it. I worked on the college literary magazine. When I left school, I continued to write poetry and get published, but there’s only poverty ahead for poets.

“While working at the airport, I had to go into Manhattan once a week for meetings. But there were many hours to kill in between. So, I took a class at Brooklyn College called American Detective Fiction taught by—I hope I remember this correctly—Professor Haig. I had never been a crime fiction fan, and never really read it. But the first three books we read were The Continental Op and the Maltese Falcon by Hammett and Farewell, My Lovely by Chandler. On the night we discussed Chandler, I came home and told my wife I was quitting my job at the airport to write crime novels. To her credit, she said to go ahead and do it. I don’t consider myself a poet because I rarely write it. I do, however, by default, write prose with the heart of a poet.”

When asked about his process, Coleman explains, “I write every morning after breakfast. I write for about three hours when I’m really intense into a project. I find that after three hours I begin to lose focus. I compare my writing routine to going to the gym. When I’m not writing according to my usual discipline, I feel guilty, like I know what I should be doing but I’m not doing it. Then once the guilt is gone, I begin to miss it. During those rare periods between books when I’m searching for a project, I feel like I’m losing my center like I’m not who I’m supposed to be.”

Coleman’s big break came when he was hired to take over the Robert B. Parker Jesse Stone series after Parker passed away in 2010. Coleman describes how it came about.

“When Bob Parker died, Joan Parker asked Otto Penzler to create a tribute project. Otto got a bunch of writers—Dennis Lehane, SJ Rozan, moi, and many others—to write essays about Spenser, Bob, and Boston. Of course, Otto asked me to do the one essay on Jesse Stone. The collection was called In Pursuit of Spenser. My assumption was that when the spot became available, someone at Putnam had read my Jesse Stone essay and thought I’d be good for the job. Wrong! At my first meeting with my editor, Christine Pepe, I mentioned my essay in the collection and she said, ‘What essay in what collection?’ Chris said that she had always liked my work, knew I was available, and thought we could work together. When I was offered the gig, I said yes in a nanosecond. Then realized I was taking over an iconic character from a grand master author.

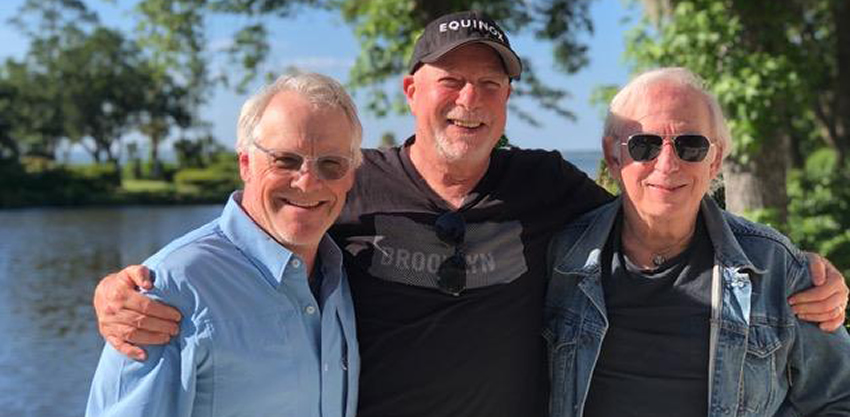

With three of the Monday night Zoom Boys: Reed Farrel Coleman, Matt Goldman, and Charles Salzberg in Hilton Head.

“I sought the advice of my old friend Ace Atkins, who had taken over writing Spenser. Most importantly, I spoke to my author friend Tom Schreck, a huge Parker fan. It was what he said to me that determined how I would handle Jesse. Tom, a huge Elvis Presley fan, said that he had seen the best Elvis impersonators in the world, but there were always a few things he couldn’t get past: 1) They weren’t Elvis, no matter how good they were. 2) Regardless of how good they were, they were trapped because they could never do new material.

“I realized I didn’t want to be a Robert B. Parker imitator because no matter how good I was at it I would never be him nor would my work be seen as anything but quality pastiche. I decided that I would keep the characters the same, but I would write in my own voice.”

After three-plus years of no new books by Reed Farrel Coleman (the publisher decided to wait out Covid, until in-person book tours could be reinstated), SLEEPLESS CITY launches in July.

“My agent, Shane Salerno, and I were kicking around ideas about a character who could work inside the system and draw outside the lines. I have written so many characters, guys like Moe Prager and Gus Murphy, who are stumblers. Well-intentioned men with big hearts and the drive to do right, but who weren’t trained to be detectives. I was excited to write a new character who is more than competent at his job, a man who has vast expertise and possesses the will to use his skills. Nick will evolve and face tough moral dilemmas.

“Of course, I wrote Jesse Stone for years. He was a skilled policeman, but he didn’t have the undercover skills Nick has, and Nick doesn’t suffer from alcoholism the way Jesse did. And Nick is mine. He’ll be a prince of the city, but rule from the shadows. I got to create him as I saw fit whereas with Jesse, I was taking over someone else’s character.”

There’s one more stop on the pizza tour: Di Fara’s. But evidently, the pizza gods are not with us today. It’s almost one-thirty, but the line waiting to order pizza is six or seven deep, and then it’ll be another half hour after we place our order. Some of us have places to go, things to do, people to see and so, reluctantly, we make our retreat. The lucky ones are those of us who had more than one Spumoni square.

But before we ride into the sunset, Reed would like to have the last word.

“I always want to say that there are so many talented writers out there besides the big-name authors we all know and love who readers should try. I could list twenty writers off the top of my head, including you Charles, I believe deserve broader discovery and love. I got lucky and landed the Robert B. Parker gig and that helped people discover my other work. Not everyone will get that chance, so I guess I’m urging readers to keep reading their favorites but to try different flavors on occasion.”

Here’s to pizza, Brooklyn, The French Connection, SLEEPLESS CITY, and friendship.

- Bryan E. Robinson - May 23, 2024

- Tom Baragwanath - February 22, 2024

- Jess Lourey - September 21, 2023