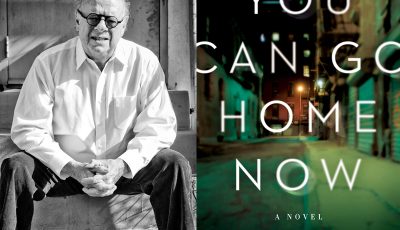

BookTrib Spotlight: Michael Elias

In Pursuit of Justice, How Far Is Too Far?

How far would you go to avenge a crime? Nina Karim is about to find out.

In Michael Elias’s YOU CAN GO HOME NOW, Karim is a homicide detective investigating the deaths of several men connected to victims in a battered women’s shelter in Queens. Going undercover, she encounters a world that leaves her shaken:

“I have been a homicide detective for five years and there isn’t much I haven’t seen in what people do to each other, but here I’m in an epicenter of crimes waiting to happen. Every one of the women have been beaten, and that’s terrible, but the fact is that they are still in danger, they know who waits for them to emerge from the shelter and the risks they take in merely stepping outside.”

Is someone helping them out, dispatching the predators? The more Karim digs, the more she feels the presence of an avenging angel—and it is a sensation with which she is all too familiar. When she was a teenager in upstate New York, a sniper killed her father, a Planned Parenthood doctor, shooting him through the kitchen window, “spilling his blood on our white refrigerator door.” The man was never caught, and it was the reason she became a police officer, not only to protect others, but to catch her father’s murderer. And when she does so, it will not be to send him to jail.

Karim has no idea of the rollercoaster journey she has just begun, of the shocks and revelations that will turn her life inside out. How far is too far? In a novel filled with twists, suspense, and unforgettable characters, she is about to find out.

“The idea for the book began with wondering about revenge and why we celebrate it in our culture and at the same time reject it as anti-social. And then the title came. I read about abused women and their children, refugees, prisoners, exiles, displaced persons, all of whom want to hear, ‘You can go home now.’ Are there sweeter words? And, as in my novel, perhaps they wouldn’t ask or care what was done to allow them to return home? I also read about the doctors, nurses, and clinic workers who risked their lives (and some lost them) providing healthcare to women, and the staggering statistics of femicide, here in the United States and all over the world. I tried to put it all together into one book.”

He did a good deal of research to get both the feel and the facts right, even though “it’s hard for a man to visit a women’s shelter. They need to be scrupulous about the safety of the women. But there’s no shortage of information and reportage about domestic violence, women’s shelters, and anti-abortion extremists. There are first-person narratives and morbid statistics. Sadly, there’s too much. The most shocking information I learned was about the danger of being married to a policeman in that context, and that there is an equal frequency of domestic abuse in the LGBQT community.”

Writing YOU CAN GO HOME NOW posed other problems, as well. Elias is the author of one previous novel, The Last Conquistador, an international thriller with paranormal elements, but for most of his life, his writing has been for film, television, and the stage, which requires a different set of skills.

“It was a big adjustment to have to fill in the blanks. Film writers are minimalists; we don’t have the same concerns as novelists. We can’t express inner thoughts and feelings (unless we use voice over), we don’t need to pay much attention to descriptions of rooms, clothes, cars, drinks, and even what people look like, or how they say lines. Try writing ‘smiles broadly’ or ‘grimaces’ for Anthony Hopkins. The director and his/her army of costume designers, art directors, location managers, car wranglers, set decorators, and stunt people don’t need you to write a room, a dress, or a fight. But novel readers do.

“I wrote Nina in the first person so I could write all the things I couldn’t do in a screenplay. But old habits and limitations stick. William Goldman said, when you write scenes ‘come in late and get out early.’

“Hollywood writing is collaborative. Most of my film and television credits are separated by ‘and’—Steve Martin, Rich Eustis, Frank Shaw, Eve Babitz, to name a few. When I wrote variety shows, people would ask, ‘Which part did you write?’ I always said, ‘Which part did you like?’

“Writing novels is singular, alone, and I enjoy sole credit. I did it all myself. No, I didn’t. I got help from Kevin Smith, other talented editors, Sara Nelson at HarperCollins, advice from writer friends, and in the case of The Last Conquistador, anthropologist Peter Nabokov, as well as more than one UCLA Inca scholar who corrected my mis-steps.

“For YOU CAN GO HOME NOW, I made sure my first readers were women and I will confess I got my male ass kicked often and deservedly, especially by Bianca Roberts, my spouse. But, in the end I think they helped me get it right.

“My writing process is to get a first draft. Bad and ugly, full of holes, handwritten notes to myself, and maybe not an ending. But there is space for a new character to barge in, an old one to demand more time, I can cut a chapter, move this to there, cut again, make it better.

“I could rewrite forever. I want it to be perfect, and I always find faults. But at some point, as Villon said, ‘Art is never finished, it is merely abandoned.’

“I’m not claiming art, but in my case it does, finally, have to be abandoned. I hate to press ‘send.’”

Elias’s influences are many. “I’ll start with my parents. My sisters and I grew up in a small town in upstate New York. Our father was the town doctor, our mother the school librarian. For all of us, it was a provincial and Chekhovian existence, my sisters and I cried ‘New York New York’ instead of ‘Moscow Moscow.’ But our parents knew how to get us out while we were still there; they gave us books. I wish they were around to read mine.

“Aside from the canon, my father handed me Michael Gold’s Jews Without Money for a social conscience, Lincoln Steffens’s Shame of the Cities, Dave Dawson in the RAF (to counter The Hardy Boys), Lenin’s State and Revolution (you get it by now that I was a Red-Diaper Baby), and Frank Harris. He also loved humor, so we read Nathaniel West, S. J. Perelman, and Ring Lardner, and we watched Ernie Kovacs together. My mother gave me Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, and Elizabeth Bowen. For a Catskill boy, Edwardian England was science fiction.”

Ultimately, they all led him to that screen and stage career. Elias has already mentioned a few of the names with whom he worked, but there’s a great many more than that—in fact, he’s led an almost Zelig-like existence. Let’s start with the stage, where at the age of 22, he landed feet first in the hot, beating heart of New York City experimental theater in the 1960s.

“I was just out of St. John’s College, teaching junior high school in the Lower East Side, and studying acting. One day walking down Eighth Street in the Village, I crossed the street for no good reason and bumped into Miriam Levine, who said she was casting a play at The Living Theatre. I went, read a monologue from Tropic of Cancer for Julian Beck and Judith Malina, and got a role in Ken Brown’s The Brig. It changed my life. I always wondered what my life would be if I hadn’t crossed Eighth Street. A friend says I would have bumped into Mike Nichols who was looking for someone to star in The Graduate.

“Being in The Living Theatre wasn’t just about theater, it was about politics, showing up for demonstrations, getting on a bus and going to Washington and marching, it was performing plays for striking Kentucky miners, and it was also about the Becks not paying taxes, and all of us in the cast going to jail with them when the IRS raided the theater.

“We did The Brig in London and Paris. I returned to New York and fell into The Judson Poets’ Theatre, where Maria Irene Fornes, Rochelle Owens, Murray Mednick, Sam Shepard, Rosalyn Drexler, Lanford Wilson, and those two magicians of Judson, Al Carmines and Larry Kornfeld, took me into their productions.

“And my time teaching in the junior high school on the Lower East Side? Twenty years later, it was the inspiration for Head of the Class. When you are a writer, your life comes in handy.”

He also attended improvisational theater workshops, where he met fellow writer and aspiring actor Frank Shaw—and his career took another turn.

“Frank Shaw and I were pretty funny together in the group, and he said we could do this professionally. I was terrified, but he told me that he had been a comedian, knew the ropes, and not to worry. He was lying. He knew less than me. But we wrote a comedy team act, went into bars on Ninth Avenue and asked if we could turn off the jukebox and do ten minutes, mostly to the jeers and catcalls of sailors and B-girls.”

Catcalls or not, they worked their way up to nightclubs and television and opening for rock acts.

“My most vivid memories are of the times we were fired.

“From The Playboy Club: right after our first show where the entire audience was composed of Japanese tourists. The manager said, ‘I don’t care. They weren’t laughing.’

“From the dress rehearsal of The Ed Sullivan Show: we followed a singer who made the audience weep with his rendition of ‘The Impossible Dream.’ We went out and didn’t get one laugh. Ed fired us from the taping.

“From a Catskill hotel: One of our best sketches in our act was about a man who walks into a bar with his pet hippo.

The bartender: ‘Male or female?’

The man to the hippo: ‘Stand.’

The bartender: ‘What’s his name?’

“The hotel owner accused us of showing a hippopotamus penis on stage and refused to pay us. It was an amazing compliment.”

And then they reached the goal for any comedian at the time: Johnny Carson! They were so good, they kept getting asked back, and after one particularly raucous performance, “we got a call from Ernie Chambers, a television producer.

“‘Who writes your material?’

“‘We do.’

“‘Would you like to come to Hollywood and write for television?’

“‘What about our act?’

“‘I suggest you give it up. Yes or no?’

“‘Yes.’

“It’s how I became a writer. The author thing took longer.”

Here are a few of the shows he worked on: All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The New Dick Van Dyke Show, Head of the Class (which he created), Steve Martin’s specials Comedy Is Not Pretty and A Wild and Crazy Guy, The Odd Couple, The Bill Cosby Show, and Pat Paulsen’s Half a Comedy Hour. His movies include Steve Martin’s The Jerk; The Frisco Kid, with Gene Wilder and Harrison Ford; and Lush Life, an award-winning jazz movie which he also directed starring Kathy Baker, Forest Whitaker, and Jeff Goldblum. Even his play, The Catskill Sonata, had star power—it was directed by legendary film director Paul Mazursky and landed on a top-ten-plays-of-the-year list.

After all that, what were some of his best moments?

“The most amazing thing was watching Forest Whitaker perform a long speech in Lush Life. When he finished, for a moment, I actually wondered who had written it. It was me, of course, but I realized that actors, great ones, take what a writer writes and elevate it beyond what I, the timid, desk-bound writer, imagined. Forest had no limits, he had no boundaries, no restraints; he explained to me what I had written.

“The second best was when Paul Mazursky directed The Catskill Sonata. He was terrific, but at one point he wanted me to change the ending. I refused. We both knew that if it were a movie, I would have been fired and he would have brought in another writer. In the theater, the writer controls the script, so I won the argument. I was right, by the way.

“More best: having my 12-year-old son see my play and say, ‘Good job, Dad.’”

There are even more memories yet to come. Next up for Elias: “A Hollywood Love Story—the adventures of a writer who spends a drunken evening with Sterling Hayden, hides a fugitive weatherman from the FBI, goes back in time and falls in love with Marilyn Monroe, makes an enemy of Michael Ovitz, and plays tennis with Abbie Hoffman while trying to figure out why his wife left him.”

Oh, that old story. Elias concludes with these words: “In Cub Scouts, I came to believe in the campfire theory of literature. Where we sit in a circle around burning embers and hear someone say, ‘Here’s a story about the fall of Troy: the hero has to make it home, and when he gets there, his house is under siege.’ You have me. I’m listening. I want to know what happens next. It made me want to tell my own.

“If what I’ve told the people reading this piece gets them to open up YOU CAN GO HOME NOW and through its 276 pages, I’m a happy campfire storyteller.’”

You can feel the embers.

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet:

- LAST GIRL MISSING with K.L. Murphy - July 25, 2024

- CHILD OF DUST with Yigal Zur - July 25, 2024

- THE RAVENWOOD CONSPIRACY with Michael Siverling - July 19, 2024