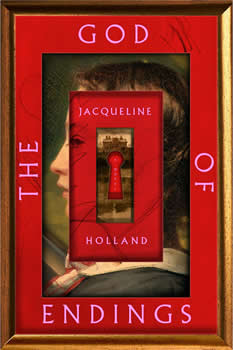

Features On the Cover: Jacqueline Holland

A Compelling and Chilling Story of Self Discovery

THE GOD OF ENDINGS, Jacqueline Holland’s debut novel, is a compelling horror story of self-discovery. A vampire, known over the years as Anya, Anna, and Collette, is seemingly both the hero and the victim of her tale. Turned into a vampire by her grandfather when she was dying of tuberculosis, she’s sent from colonial America to the forests of Slovenia and her new family of Ehru, Vano, and Piroska to learn exactly what kind of existence she’s been signed up for.

It’s an existence where she’s become an orphan, an artist, a war survivor, and a wilderness isolationist. Now she’s a teacher who owns and runs a very successful, selective preschool for children ages three to five in Millstream Hollow. It’s a comfortable life she cherishes. One she doesn’t want to lose.

But hanging over Collette like storm cloud is the Slavic god Czernobog, the God of Endings. A mythical deity who returns again and again to take away everything that Collette loves. This time, hints of his appearance also bring intense cravings for blood, followed by blackout periods where Collette wakes up muddy, bloody, and wounded.

Those around her are dying and then of course, there’s the complicated relationship she’s forging with the parents of one of her favorite students. Collette’s afraid she’s becoming the monster she’s fought her whole life not to be.

Here, The Big Thrill sits down with Holland to talk about her thrilling new contribution to vampire lore.

At its core, THE GOD OF ENDINGS is a vampire novel. How is your vampire world different from other novels?

There are very devout vampire fans who “know the rules,” and have really strong opinions about adhering to those rules or breaking those rules. And then there’s also sort of more casual readers who … know they’ve heard of the rules. Like, is garlic going to be in here somewhere or are there going to be stakes in people’s hearts? I let myself sort of reinvent the wheel. I tried to treat my vampires as very organic biological beings, so they really aren’t terribly mythical or magical. They’re just a certain kind of organism.

These vampires live off blood. That’s how they stay alive. And they have immortality. They also have some exceptional physical traits: strength, speed, and things like that. But they can walk around in daylight, they have reflections in the mirror, but there isn’t a whole lot of the packaging that sometimes goes along with vampires. I tried to take a very realist approach and make them as believable and realistic as possible, which I imagine some people are going to enjoy.

The interesting thing about vampires is that there’s a super long history. Vampires come from lore. Most of my research was into vampire lore and the cultures and the stories that people told when they believed vampires were a real thing. And a lot of those stories are really disparate. The traits for vampires are not all that consistent, aside from drinking blood and being pretty uniformly nasty, which is a convention I broke as well. And so I actually felt pretty okay about it [breaking conventions] because I feel like that sort of hardening of the genre is something that’s happened a little more recently, and that there was something older that I could tap into that allowed for more mystery and some unexpected characteristics.

Anna/Anya/Collette see herself as a monster. Why would she put herself in close daily proximity to children given the risk she poses?

Collette (I call her Collette because that’s how she first spoke to me) has very dual nature. She has a monstrous side, but she also loves children. She’s drawn to them, she cares for them, and she’s chosen this role specifically because it’s the deepest and most intimate human relationship she can have without the risks that come from relationships with adults.

She’s tried to live among people, and she could only do it for so long because she doesn’t age and everyone else does. People ask questions and people get wise, but children don’t. And in a preschool, they come and go, and their parents come and go, too, so it really ends up being sort of the best situation for her.

It seems like she has a love/hate relationship with humanity.

Don’t we all?

Ha! Yes. She spends decades apart and alone, then she’ll assimilate for a few years until something goes horribly wrong, her happy time with humanity ends, and she isolates herself again. Even running the preschool seems to be an uneasy truce. The children come for two to three years and then move on. She doesn’t, or can’t, get attached to anyone.

It’s funny, as you describe that, I feel like that could be me in high school a little bit. She does have concrete constraints because of her vampire nature, but she’s not really dealing with anything that we all don’t deal with in some sense, because we all deal with loss. Many people, when they lose things they cherish, are embittered by it and it does make it harder to … let yourself become attached.

That’s part of why this is a vampire novel. The vampire condition … aggravates some fundamental traits of human experience and draws them in sharper relief and allows us to think about those experiences and those emotional challenges we all face.

In a way, she’s in denial of her own vampire nature, and yet she’s allowing it to construct who she is as well. She’s giving and loving, and her very core is human. She has human emotions and feelings of wanting to be accepted and to feel love. Yet, she is allowing the vampire part of her nature impede her ability to give and receive affection. Then she wakes up in the morning covered in mud and blood and scratches and other wounds. Don’t you feel like that just sort of is reinforcing the whole “I’m not worthy to be part of humanity” for her?

Yeah, I do. I think that is something that I’ve done. I have fixated on the dark parts of myself and tried to pack them away out of sight and hide them from other people. We self-flagellate a little. Having these flaws and the responses to the darkness in ourselves, I think, often exacerbates the situation. It makes us feel more monstrous and creates a cycle where we are unable to give what we have to give because we’re so fixated on the broken parts of ourselves.

Given her determination to stay removed from humanity, what is it about Leo, the sickly boy in her preschool class, that draws her in?

I think she knows early on that Leo is the most dangerous kind of child for her. She has a policy of only accepting healthy, happy, well provided for children who are not going to suffer. [Children] who are not going to be in pain because she can’t handle watching pain anymore. She’s known a lot of children who have suffered, and she has in her character a fierce warrior side. But in the past, she’s largely failed in her attempts to defend and protect the vulnerable.

Leo is so dangerous because she can smell the weakness and the vulnerability on him immediately. The reason she avoids vulnerable children is because she’s drawn to them and she wants to protect them. So when she meets Leo, he sort of slips under the fences and almost as soon as she’s met him, it’s too late. She’s drawn to his [artistic] talent and she’s drawn to his sweetness, and unfortunately, she’s drawn to his vulnerability as well.

You have the god Czernobog, who is the God of Endings, as a character in this story. Collette fears him coming in and taking away her comfortable life. But then we learn there is this duality to endings—the end isn’t really the end. What do you mean when you talk about the non-finality of endings?

Czernobog starts out the story representing destruction and loss, and inevitably having the associations of pain and anguish to go along with that. If you live long enough, you’ll experience a lot of that. You don’t even have to live that long to experience loss. Things are impermanent. Nothing is guaranteed forever. And it’s very easy to become fixated on the loss of good things.

From the pain and loss you can have almost a hollow carved out of you that creates a longing and an ache. So, when you receive something new it is an incredible joy. There’re so many truisms that that we can drop in there, you know? [For example,] it’s better to have loved and lost. But if you never lose, what you have becomes of less value.

How did you learn about Czernobog?

This was really fun. I was working at a wine restaurant in Chicago and I had a coworker there who was from Moldova. As we’re polishing wine glasses, he would tell me about all the bogs. Bog is Russian for god, and there’s Belobog and there’s Czernobog, and there’s so many gods. He would talk about how they’re related and all these different [mythologies].

I was trying to write this section and I had this intense interest in taking Collette to this place deep in the forest that sort of reminds me of Sleeping Beauty tucked away in the cottage with the fairy godmothers. And as he started telling me about [Czernobog], my imagination just started going wild and I started researching, and the research was even more fascinating. And it just fit. It all clicked together magically.

You talk about light and dark being necessary for life and art to be exciting and not “blah.” What about his contrast is necessary for life not to be “blah?”

My husband is a fine art painter. We’ve been together for 13 years, so for a very long time he’s explained to me how you paint and the fundamentals of visual art. He explained that when you are painting a painting you have to first establish the lightest light and the darkest dark, and that’s going to be the scale that you have to work within.

You are more aware of the light when it is placed beside darkness, and I think that translates into fiction. I don’t like books where only pleasant things happen. I don’t enjoy them. I don’t even find the pleasant things pleasant because it just blends together. It all melds, and becomes nothing.

I think some of these laws apply in a deeper way that maybe can’t even be understood, but it’s about the where our brains and our hearts take in information and make sense of it and give it value. If nothing bad ever happened to us, nothing good would ever happen to us either, because we wouldn’t have a scale of comparison.

What’s next for you?

I am working on a new novel. It’s been interesting to have my debut be a fantasy novel, because I think of myself as a science fiction writer. I’m working on a science fiction novel that I’m very excited about. And I look forward to kind of stepping into that realm where I feel like I’ve always been, but having readers come along with me.

- THE GOD IN THE SEA with Paul Kemprecos - April 4, 2024

- FOR WORSE with L. K. Bowen - April 4, 2024

- HIT AND RUN with Vincent Zandri - April 4, 2024