Debut Spotlight: Lara Bazelon

Motherhood Is a Double-Edged Dagger

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

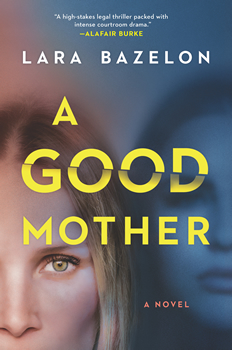

Self-defense or cold-blooded murder? That’s the question behind defense attorney, journalist, and author Lara Bazelon’s debut legal thriller A GOOD MOTHER.

Deputy Federal Public Defender Abby Rosenberg receives the case of a young mother who stabbed her soldier husband to death. Luz Rivera Hollis admitted to the crime, calling 9-1-1 herself right after it happened. Luz claimed she was protecting herself and her newborn infant.

Abby is herself pregnant and should give birth within a few weeks; her boss will then reassign Luz’s case to a newbie attorney in their office, Will Ellet. Abby has promised her partner, US Marshall Nic Mulvaney, that she’ll take her full months-long maternity leave after the baby is born. But when their son, Cal, is only weeks old, Abby finds she can’t disconnect from Luz’s trial. She feels a bond with this new mother who’s accused of murdering her husband, and she knows she’s the one who must represent her.

Abby persuades her boss to let her handle Luz’s defense, but he insists that Will must be her co-counsel. Nic can’t believe Abby has let her ambition impede bonding with their baby. Abby hates to leave Cal so frequently, but she just can’t stay away from the case. The long days and nights preparing for trial leave Nic bitter and Abby conflicted.

Abby loves Cal more than anything, but she knows she also has to be herself—a criminal defense attorney.

As the trial continues, Abby must deal with Luz’s lies, Will’s unethical conduct, the trial judge’s bias, and Nic’s belief that she’s a bad mother. She’s near the breaking point from the stress. Abby proved in her last trial that she’s no stranger to using whatever means necessary to defend her client. And after her previous trial, she’d developed an alcohol addiction.

But that was before she got pregnant with Cal. The baby saved her from herself. She’s a stronger person now. At least, she hopes she is.

Can Abby continue to represent the mother who might not be the battered woman she claims to be? Can she continue with the trial and still prove her own dedication to motherhood?

“In the early 2000s, two of my former colleagues at the Office of the Federal Public Defender in Los Angeles tried a case in which their client, a young mother, was accused of stabbing her soldier husband to death on a military base,” says Bazelon. “I watched every day of the trial, riveted. The questions at the heart of the case—was the client a so-called ‘battered wife,’ was her life really in danger, was her sorrow and remorse genuine?—played out in the courtroom in very unexpected ways. I always thought the case had the makings for a compelling legal thriller.”

As a former federal public defender, Bazelon incorporated herself into Abby’s character, then super-sized it.

“Abby is like me, but EXTRA. She’s more ruthless, single-minded, sharp-edged, and a far, far better lawyer,” she says. “She is also a lot more reckless, and I like to think has more blind spots. Her struggle to balance her ambition with being a mother and her determination to win because she thinks her cause is righteous is very much in keeping with my life experience. The sexism and judgment she faces inside and outside of the courtroom are like what I’ve experienced as a female trial lawyer and what so many other female trial lawyers still experience every day.”

Besides Bazelon wanting to put her “readers on a rollercoaster ride that keeps them breathless,” there are issues she’d like people to consider when reading A GOOD MOTHER.

“I also want readers to contemplate bigger questions, even as they experience the stomach-dropping plunges and sharp turns,” she says. “Like the best roller coasters, I want to emotionally flip them upside down so they’re reexamining fixed beliefs from a fresh perspective. What does an effective trial lawyer look and sound like? What does it mean to be a good mother? And of course, did she do it? I want readers to grapple with these big questions and come to their own conclusions.”

In real life, Bazelon is an advocate for racial justice and indigent clients. She incorporated these issues into the narrative of the novel.

“It was important to me to have diverse characters because that reflects reality. For several reasons, including systemic racism, it is an established empirical fact that a disproportionate number of people who face criminal charges are people of color,” she says. “So, too, is the diversity of the bar in this area of practice. The Office of the Federal Public Defender in Los Angeles where I used to work was diverse. The head of my office was a woman, and the deputy chief was a man of color. (Today, they are both judges.) There was also diversity in the US Attorney’s Office.

“I wanted the real-life complexity and nuance of race and gender to be present in the novel, whether it was exploring explicit and implicit biases, courtroom power dynamics, or the constant need for the attorneys to combat stereotypes—about themselves and about the accused—that were lurking just below the surface. I didn’t want the book to be a polemic, and it was important to me that I made every single character complicated and complicating, as all humans are.”

Before she became a law professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law, Bazelon was a deputy public defender and the director of an LA-based innocence project. Photo credit: Kim Fox for Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

Bazelon addresses how a woman’s ambition and motherhood can intertwine, causing some to make unfair judgments about mothers. She’s even working on a nonfiction title about this subject.

“To quote my protagonist, Abby Rosenberg: ‘There is nothing like the judgment we visit on mothers.’ Never more so when they are ambitious mothers,” she says. “The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word ‘ambitious’ as ‘having or showing a strong desire to succeed.’ Sounds reasonable enough, right? But when people apply the term to women, it often serves as a modern-day scarlet letter, marking them as cold, calculating, ruthless, selfish, and cruel. That’s particularly true when we’re talking about ambitious women with young children, their work perceived as posing an existential threat to their family unit, as toxic and illicit as a love affair.

“My take is quite different. I think that motherhood and ambition can not only coexist but can mutually reinforce each other. For some mothers, being able to pursue their professional ambitions makes them happier people and therefore better parents all around. That is the argument I make in Ambitious Like a Mother, where I write about my mother’s story, my story, and the stories of dozens of other women I interviewed, while also looking at the sociological research and getting their children’s perspectives.

“But with my novel, I wanted to push my thesis all the way to the breaking point. One joy of fiction is that it lets me create the most extreme and forceful rebuttals to my own cherished beliefs.”

Bazelon is also busy working on her next novel and gives us the lowdown.

“A star college football player’s bright future in the NFL is imperiled when explosive cross-racial sexual assault allegations emerge against him and his friends. Is the girl lying? Are they? Who deserves to pay? Stay tuned!”

Does Bazelon have advice for other writers, especially those juggling their writing careers with kids or other careers?

“I hesitate to provide writing advice because I know every writer has their own process. But personally, I find writing excruciatingly difficult. I’m compelled to do it, and yet to this day, am a terrible typist because the words come so slowly. Writing is like exercise. Unless I establish a routine, I won’t do it. So I establish a routine.

“Six months ago, my friend Valena and I developed a Zoom writing schedule. We write three times a week at a set time for an hour each time. We check in briefly, then turn off the video and the audio and write. When I get frustrated, her picture in the corner of my screen keeps me motivated. Knowing she’s there, engaged in the same struggle, makes me feel supported and less alone. At the end of the hour, we check back in.

“Sometimes we feel triumphant, sometimes crappy. It’s always helpful to share and commiserate. The schedule forces me to write regularly, which I doubt I would otherwise do, especially when life gets very hectic at home or at work.”

And finally, what about Bazelon might her fans not already know?

“I sucked my thumb until I was in sixth grade, and I wish I still did. I will never find another habit that was so comforting. I’ve tried taking it up again, but the feeling is gone. Now I shred things.”

- Flora Carr - March 29, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: EVERYONE IS WATCHING by Heather Gudenkauf - March 29, 2024

- B.A. Paris - February 22, 2024