Africa Scene: Peter Kimani

An Eye-Opening Collection Set in Nairobi

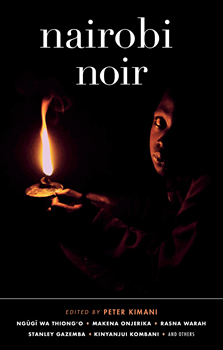

In their City Noir series, Akashic Books has been bringing out some eye-opening collections from Africa. The first sub-Saharan volume was Lagos Noir, fascinating in its diversity and uniform high quality. Accra Noir and Addis Ababa Noir are ahead—but NAIROBI NOIR is here now. The editor, Peter Kimani, is a leading Kenyan journalist, academic, poet, and novelist, and his book Dance of the Jakaranda was shortlisted for a number of major prizes. In NAIROBI NOIR, he’s assembled a diverse set of Kenyan authors to take a hard look at their city. As Kimani puts it, “these are very illuminating optics.” Publishers Weekly summed it up this way: “Racial, religious, and class divides are acutely observed in the 14 new stories from Kenyan writers…Crime fiction fans will find much to savor.”

Writing of the city and the collection itself, Kimani concludes his introduction with: “The Green City in the Sun (Nairobi) may have turned into a concrete jungle, but it is still enchanting. And the spirit of its forebears, the hunters and the herders and the hunted, still lives on…”

Part 1, The Hunters, begins with Winfred Kiunga’s “She Dug Two Graves.” It starts with the brutal murder of a young man, but the story is about his sister’s bittersweet revenge.

Kevin Mwachiro is a broadcaster, writer, and poet. His story, “Number Sita,” is told by one of three close mates. It’s about the lesbian woman who befriends them. And about coming of age. Unforgettable.

In “Andaki,” banker and author Kinyanjui Kombani tells us of a house of fugitives hiding from the police. The shocking part is why…

Troy Onyango is a lawyer and writer of award-winning short stories. “A Song from a Forgotten Place” is the tale of what it means to be a homeless woman on the streets of Nairobi.

Winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing, Makena Onjerika tells us what goes on in a “Mathree”—one of the ubiquitous minibus taxis that ply their trade around African cities with little regard for the rules of the road or the safety of their passengers.

Peter Kimani himself kicks off Part II, The Hunted, with “Blood Sister.” A classic love triangle story? Anything but.

Faith Oneya’s “Say You Are Not My Son” and Wanjikũ wa Ngũgĩ’s “For Our Mothers” are sad stories of where good intentions force you when you’re desperately poor.

“Plot Ten” by Caroline Mose takes us to a plot in Mathare where the residents protect themselves, except from the police. Then a murder happens.

Rasna Warah’s “Have Another Roti” shows how you don’t have to be forced from your homeland to be a refugee. Warah has worked with the United Nations and authored five nonfiction books, including Mogadishu Then and Now. She knows what she’s writing about.

Part III, The Herders, starts with J. E. Sibi-Okumu’s “Belonging.” He has wide talents as an actor, playwright, and columnist. This is his first attempt at a short story. Clearly his talents extend to that too.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is one of the world’s leading writers of literature and has been nominated for the Nobel Prize more than once. “The Hermit in the Helmet” is deep and delightful. The premise is fantastic, but the people and what motivates them are all too real.

Stanley Gazemba is a prize-winning novelist. “Turn on the Lights” features two women trying to make ends meet by selling illicit alcohol. Once the police catch them, it all goes awry.

The last story in the collection is by Ngumi Kibera, a prolific writer of fiction. “The Night Beat” is about the police again, but here we meet an honest one for a change.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Kimani shares insight behind the construction of this eye-opening anthology.

What motivated you to edit a collection of stories set exclusively in Nairobi?

I was commissioned by my publisher, Johnny Temple, to put together NAIROBI NOIR. One key consideration is that all stories in the anthology have to be set in one city.

You are a senior and well-known author and journalist, but there is a broad spectrum of authors here, from writers just starting out to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Did you invite authors to contribute, or did you open it to anyone?

I did both. I reached out to individual writers, but also sent out calls for contributions. One contributor, for instance, attended my creative writing workshop, while another belonged to a reading club that hosted me. I’d use such forums to solicit for contributions. Nearly half the contributions did not make the grade.

One of the most satisfying elements of the anthology is that about half the contributors are first-time writers, appearing in the same collection as one of the world’s best-known living writers, Ngugi wa Thiong’o! As one contributor confessed, he was happy I did not divulge who the other contributors were, for he would have felt very intimidated.

NAIROBI NOIR is very dark. Most of the stories give a depressing view of the city with its police corruption and extremes of poverty. (A notable exception is the whimsical gem from Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.) I presume the authors chose what to write within broad guidelines. Were you surprised by the approach they took?

I left it to the writers’ imagination to envision stories that gave life to the spaces that they inhabit. Surprisingly, they all gestured toward issues of crime and punishment, law and (dis)order. These are very illuminating optics, for this is a city founded on strife. The British colonial authorities enacted dubious land treaties that dispossessed the original inhabitants, and this noir spirit lurks in virtually every corner of the city. Even as I write this, in the shadow of a pandemic, there are distressing reports of police receiving bribes from folks who want to escape lawful quarantines—to return home and potentially, and knowingly, spread disease. Then there are government officials lining their pockets with funds meant for the most vulnerable, while homeless Kenyans have had their shanties demolished, rendered homeless, yet again.

To survive such vicissitudes, Nairobians use humor to survive a system that undermines their humanity. I believe there are adequate doses of humor in the stories to keep a reader entertained, while placing their pulse on the heart of the matter.

Your own story—”Blood Sister”—is one of the few in the collection that links the rich and poor, white and black, local and foreign. The love triangle that your protagonist engineers leads to surprising reactions and outcomes. Did you want to show that emotions and results depend as much on the environment as on so-called human nature?

I have no set objectives when I set out to write a story. I write to discover. So I am curious what readers will discover in the story.

Many of the writers in the collection are published internationally as well as in Kenya. The collection displays the abundance of talent—do you feel Kenyan writers get adequate recognition in the international markets?

As I said, half the writers in the anthology are writing for the first time—and will be read beyond the Kenyan borders. As long as initiatives such as NAIROBI NOIR are available to more writers, more Kenyan writers will be in circulation internationally.

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024

- International Thrills: Why Read African Thrillers? A Year in Review - December 15, 2023