Africa Scene: Michael Niemann

Where Global Forces Meet Ordinary Lives

For more than 30 years, Michael Niemann has been interested “in the sites where ordinary people’s lives and global processes intersect,” and he has traveled and written widely about Africa and Europe as part of his academic work in international studies. Along the way, he has helped students of all ages and backgrounds to understand their role in constructing the world in which they live and to take this role seriously.

So it may seem strange that Michael turned to writing thrillers, but his experiences—particularly in Africa—inform his work and lend a richness to his characters.

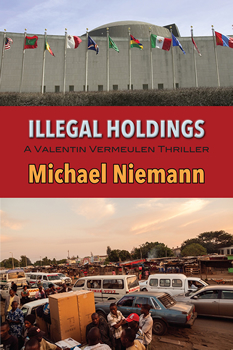

His debut novel, Legitimate Business, first published in 2014 and reissued last year, featured Valentin Vermeulen, an investigator for the UN. It’s set against the sandy hopelessness of Zam Zam camp in Darfur. The sequel, Illicit Trade, also released last year, addressed human trafficking from Kenya. This month the third Vermeulen thriller, ILLEGAL HOLDINGS, comes out. It takes place in Mozambique against the backdrop of the vexed issue of land rights. Vermeulen is auditing a small aid agency, which has apparently misappropriated five million dollars, but the corruption goes much further than the missing money.

You are clearly familiar with Mozambique and understand its complex issues. What made you decide to set one of your novels there?

Mozambique was the second African country I ever visited. I spent time at the Centro de Estudos Africanos in Maputo, the capital, as part of my dissertation research. While there, I also had a chance to roam the city. Despite the poverty and deprivations of the civil war that was still going on, I met some of the most warm and generous people there. It’s also a country with a fascinating history. Before colonization, it was part of a vast Indian Ocean trading world. Colonization by the Portuguese was brutal and began earlier than elsewhere in southern Africa. Their first settlements there predate even the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck in Cape Town. Its struggle for independence was led by Eduardo Mondlane, an assistant professor of anthropology from Syracuse University.

The second reason was the worrisome development of foreign land acquisitions on the African continent after the 2007/08 crash. Mozambique is one of the countries where biofuel companies, hedge funds and others have bought vast stretches of land. I thought that was a suitable topic for a thriller.

Pungwe bridge

Vermeulen seems happiest when he is operating where “ordinary people’s lives and global processes intersect” and much less comfortable in the hierarchical structure of the UN in New York. Once he reaches a country, he tries to understand the people. Do you see a lot of yourself in him? (Hopefully you didn’t spend your career being shot at!)

Of course, his overall concerns are rather similar to mine, we both have a strong interest in justice. But I purposely chose a protagonist that was rather different from me—being shot at is only one of the crucial differences. The closest I ever was to bullets was my mandatory service in the German army. But Vermeulen’s MO is really more common sense. People don’t do things randomly, they do them because, at the time, the choices made sense in their context. So unraveling a mystery really means understanding people. That’s even more crucial when coming to a country and culture different from one’s own. Vermeulen has been in enough strange circumstances to realize that asking questions is the best starting point for an investigation. Any good investigator, police officer or private detective knows that.

ILLEGAL HOLDINGS features three strong female characters, Aisa, who is the director of a small NGO (Nossa Terra) concentrating on resettling people on the land; Isabel, the director of the Maputa branch of a big funder (Global Alternatives); and Tessa, Vermeulen’s on-again, off-again girlfriend. Was it part of the plan to juxtapose these very different women?

I wish I could claim so much plotting, but two of the female characters developed as the novel progressed. Tessa was a given since she’s a recurring character. Aisa Simango is a composite of the many strong women I have met during my work on the continent. For example, in 1999 I visited a number of human rights organizations in four southern African countries for a project documenting regional approaches to advance human rights protections. Every one of these was led by women who were in the forefront of the struggles to make lives better for their compatriots. Nossa Terra was inspired by the Union of Cooperatives, a female run organization that provided much of the food for Maputo during the civil war.

Isabel LaFleur really popped into my head as I began fleshing out the staffing of Global Alternatives. There is a general presumption that people working in development aid are compassionate individuals. So I asked, “What if that person is a blatant careerist?” She is a strong character, but only in the sense of looking out for herself.

Land rights, and the appropriate use of the land, is a contentious issue throughout Africa. It’s a flashpoint. Is that what suggested the theme of the novel to you?

The short answer is yes. But the question of land took on an even more dramatic role after the 2007/08 great recession. Part of the chaotic global response to the crisis led to an increase in world food prices. Investment funds around the world, desperate for new investment opportunities began buying land around the world promising their investors high returns. Some of these land deals involved so-called sovereign wealth funds from the Arab world.

Access to land and control of land has long been a crucial issue. The imposition of market-based solutions in societies where much of the land tenure was based on traditional and reciprocal approaches has created a complex patchwork of rules. Foreign actors have learned how to exploit that, more often than not, at the expense of the people working the land.

In contrast to your last book, almost all of ILLEGAL HOLDINGS takes place outside of the United States. Yet Vermeulen is as much in danger in the US as in Mozambique. One may think of countries like Mozambique as corrupt and dangerous, while in the US one is protected by the rule of law. You seem to be saying that it’s only a matter of how powerful the villain is rather than where he or she is operating. Is that correct?

Yes. The rule of law is a noble concept, but when corrupt practices are made legal, what does it really mean anymore? In the U.S., passing legislation that benefits narrow interests who offered campaign contributions is not called “corruption.” It’s been legalized and is called “constituent service.” I understand that a police officer who accepts a bribe and lets a motorist off undermines public trust in institutions. When powerful actors do what amounts to the same, there’s rarely a quid pro quo. That kind of corruption operates on consensus and shared values. As a result, it is untraceable but equally damaging to that trust.

There’s a great paragraph in John Le Carré’s The Constant Gardener that highlights how it works: “And so it is done. Not by the boss or the sub-boss or the lieutenant or the sub-chef. Not by the corporation. Not by anybody at all, actually. But still it is done. There are no papers, no checks, no contracts. Nobody knows anything. Nobody was there. But it is done.”

KillBill is an interesting character. Fixated on a warrior life that he knows only from the movies, he joins a vicious gang to practice it, but it is actually the honor that he seeks. He is easily switched to Vermeulen’s side. Is it broken families and soaring youth unemployment that leads to KillBill’s sort of life?

Poverty and youth unemployment are issues that affect countries all over the world. It is not limited to Mozambique. An interview in The Big Thrill isn’t really the space to address these issues in depth. Let me say this much. For many people around the world, the choices have been shrinking rather than expanding. It is a testament to the failings of many institutions and ideologies. Youths like KillBill exist because they and their family’s choices were so narrow that hustling remained the only choice to stay alive. To quote a line of Zimbabwean musicians Comrade Fatso & Chabvondoka, “When the poor hustle, they criminalize it.”

What’s next for Vermeulen and Tessa?

The fourth Vermeulen novel is set in southern Turkey in the midst of the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis. The UN Refugee agency is spending large amounts of money to support the millions that flow across the border. When Vermeulen checks a local NGO, it turns out to be a front for organized crime. I’ve just finished the first draft.

_______

Visit Michael on his website, join him on Facebook, and follow him on Twitter (@m_e_niemann).

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024

- International Thrills: Femi Kayode - March 29, 2024

- International Thrills: Shubnum Khan - February 22, 2024