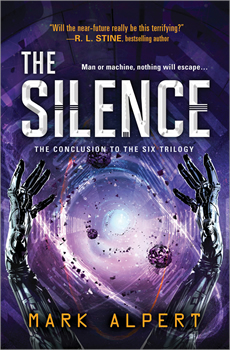

The Silence by Mark Alpert

The Role of Real Science in Thrillers

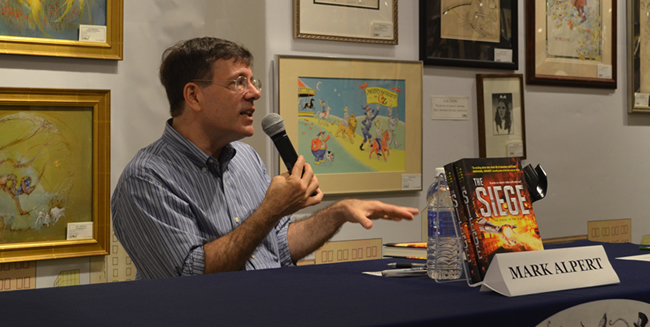

If a decade of writing science thrillers has dulled Mark Alpert’s enthusiasm for his craft, you certainly can’t tell it from speaking with him. When he talks about his latest release, THE SILENCE, Alpert doesn’t offer any of the rehearsed answers to which popular novelists sometimes default. Instead, he gives an enthusiastic crash course in brain science, nanotechnology, and gene editing—not to mention the alchemy of splicing those lofty ideas into fast-paced, intensely readable thrillers.

Alpert, a self-described “lifelong science geek,” spent years oscillating between the worlds of science and writing before he settled into a career that combined the two disciplines. He holds a degree in astrophysics from Princeton, and another in poetry from Columbia University. He worked as a reporter for newspapers and magazines before becoming an editor at Scientific American in 1998; ten years later he published his first novel, 2008’s Final Theory.

This month finds Alpert wrapping up his first sojourn into yet another world: young adult literature. Alpert’s third YA thriller, THE SILENCE, hits bookstores on July 4 from Sourcebooks Fire. It’s the final installment in a trilogy that began with The Six in 2015 and continued last year with The Siege. (If you missed those first entries, you’re in luck; the publisher released paperback reissues of both volumes in June.)

Like many writers, Alpert credits his kids, and their reading habits, with pulling him into the realm of YA fiction. “I have a 17-year-old boy who’s going off to college in the fall and a 15-year-old girl who’s a sophomore in high school,” he says. “My daughter’s a big reader; my son, a little less so. But when he found a series he liked, he really devoured it. He loved the Maze Runner series and a couple of others. I thought, well, I’ll try to write a series sort of like that, and I’ll make it a science thriller, like my books for adults.”

The result was The Six, a sci-fi actioner about six terminally ill teenagers who participate in an experimental U.S. Army program that uploads their minds into sophisticated, combat-ready robots. Like most of Alpert’s adult fiction, the story can be traced back to his days as a science editor.

“When I was at Scientific American, I would often write or edit stories about robots,” Alpert remembers. “Companies would send their latest robot to the magazine so we could test it out. And then I’d also read The Singularity Is Near by Ray Kurzweil, and that’s kind of a cool, freaky idea—that you could somehow record everything in your mind. If you could actually figure out how the brain works and how it encodes your thoughts, theoretically it’s possible to record all that information and then put it in digital form and put it in a robot. It’s a kind of technological immortality. And so I thought, wow, if I was gonna write a book with teenage protagonists, it would be interesting if maybe they were the first ones to make that leap from human to robot.”

The trilogy centers on Adam Armstrong, a sports-loving boy forced into a wheelchair at the age of twelve by muscular dystrophy. By the time he’s 17, Adam’s disease has advanced to the terminal stage; to save his life, Adam’s scientist father uses experimental brain-imaging technology to scan the teen’s brain and transfer his consciousness to a nine-foot war machine.

The setup might sound farfetched given the trilogy’s contemporary setting, but the human-to-robot transformation at the heart of the books has roots in existing technology. As with his adult novels, which include the 2013 techno thriller Extinction and the 2016 first-contact yarn The Orion Plan, Alpert says it’s important to him to incorporate real science into every aspect of his YA adventures. For THE SILENCE and its predecessors, he found footing in the BRAIN Initiative, a $100 million brain-imaging project spearheaded by the Obama administration in 2013. While the technology is being developed with an eye toward medical applications such as cancer and Alzheimer’s treatment, Alpert’s writer brain went in another direction.

“One of the technologies they’re looking at is using nanoparticles that will only chemically bond to tumor sites,” he explains. “So you inject these nanoparticles into the body, and they find the tumor, and then you take a specific kind of light to selectively heat those nanoparticles and eliminate the tumor. This is a real technology. I remember writing about it at Scientific American. And that’s the technology I used to image the brain [in the Six trilogy].”

But for all the heady science and spectacular action sequences—THE SILENCE finds Adam doing battle at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, in surreal virtual reality landscapes, and even inside the body of a dying girl in a Fantastic Voyage-style microbiological showdown – the biggest challenge the kids face is retaining their humanity.

“That’s a big struggle in these books,” Alpert says. “Once you become a robot, you have so much power, and you can move from one machine to the next, and your mental abilities are incredible. But can you maintain your humanity when you’re so powerful? That’s what Adam and the other characters struggle with.”

And while that focus on humanity over hardware has helped the books resonate with young readers, Alpert has found that kids are just as intrigued as adults by the sophisticated science that underpins his work.

“I’m a true believer in not dumbing down the books for young adults,” he says. “I think they can have just as much science as adult novels. I get most inspired when I see a kid who’s read the books and they totally get it—they understand every single bit in it and have actually thought the matter through more than I have. I love hearing that, because then you realize, these kids are smart. If they’re passionate about it, they’ll understand it better than I can understand it. That’s my goal, I guess.”

- Between the Lines: Rita Mae Brown - March 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Stephen Graham Jones - January 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix - December 30, 2022