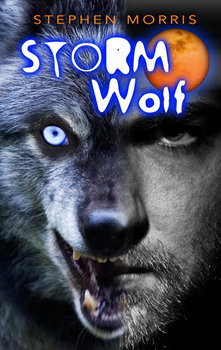

Storm Wolf by Stephen Morris

Most of the “werewolf rules” we’re familiar with— such as transformation during a full moon—spring from the movies. In his new book STORMWOLF, Stephen Morris takes readers into an urban fantasy world where older werewolf myths are in play. You might say it’s a wild ride.

Morris, who holds degrees in medieval history and theology from Yale and St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Academy, draws on his study and research of medieval magical practice for the tale of Alexei, a young man who “breaks the terms of the wolf-magic he inherited from his grandfather and loses the ability to control the shapeshifting, becoming a killer and slaughtering his neighbors, his friends — even his family.”

He’s soon driven to wander into encounters with other wolf practitioners in a tale that garnered high marks from Kirkus Reviews:

“Morris’ werewolf isn’t a fur-coated romantic, but a refreshingly murky protagonist who’s both flawed and sympathetic; he kills innocents, but never intentionally. There are quite a few werewolf onslaughts, which the author unflinchingly portrays as bloody and brutal…. A dark supernatural outing, featuring indelible characters as sharp as wolves’ teeth.”

Morris is a former priest who served as the Eastern Orthodox chaplain at Columbia University, and a Seattle native making his home in Manhattan with his partner, Elliot. He’s written non-fiction of the Late Antiquity and Byzantine church life and has also penned a trilogy, Come Hell or High Water.

This month, The Big Thrill posed a few questions to Morris about STORMWOLF.

Your book looks at aspects of werewolf lore not often portrayed in film and fiction. Tell us a little about the regions you’re delving into for the story.

It just so happens that Estonia, although little known to non-Estonians, has a fascinating, although difficult-to-trace, heritage of folklore and legends that set it apart from not only its Baltic neighbors (Latvia, Lithuania, Russia), but from almost everywhere else; traditional beliefs and practices survived in Estonia for much longer than in other regions of Europe. These traditional Estonian legends and folklore were primarily handed down via oral tradition until very recently; Estonia was a pre-industrial, rural society until 1900.

Latvia and Lithuania were similar in that they also had large pockets of pre-industrial culture surviving until nearly 1900 as well. The natural beauty of the Baltic States has to be seen to be believed. In the forests and fields of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, it is easy to believe that werewolves and other mythic characters are hiding just behind that tree or around the bend of the road up ahead.

Fill us in a little about the authentic werewolf and shapeshifting lore you’re drawing upon.

I picked up a book one day about folklore as I was researching another project and found a brief reference to the Estonian version of werewolf folklore: in Estonia, werewolves could fly and would drive away the storms that would otherwise devastate the farms and destroy the crops. They killed storm clouds and ate weather devils—not their neighbors. They were heroes, not monsters.

Because they were heroes, everyone in a village or district knew who the local werewolf was. It was an honored position. (The only other place that had an even slightly similar version of werewolf folklore is a small Italian region northeast of Venice where the werewolves are called “good walkers” and drive away witches that attempt to destroy the crops.) Estonian werewolves were so unlike their more commonly-known cousins in other parts of Europe that it almost seems a shame to characterize them all with the same moniker.

Do you feel you’re taking something old and making it new again with the original legends?

I think that we are discovering that the world of legend and folklore is much more complex than we first suspected; it is as big and wonderful and diverse as the physical world that we are exploring and discovering more about every day. Werewolves are a good example of that. The Hollywood portrayals were based on tales of monsters attacking and killing, but even in the Middle Ages the official teaching of the Church was that there were no such thing as werewolves and that shape-shifting was impossible. Most people today are unaware of that and simply think that medieval people were so much more gullible than folks are today. We can take the old and appropriate it in new ways to tell stories that resonate with modern experience, but we need to make sure that we really understand the old stories first before we begin to play with and adapt them.

Tell us a little about your protagonist, Alexi. He’s the descendant of a long line of practitioners of wolf magic, but things are going a bit wrong for him.

Alexei inherits a magic wolf pelt from his grandfather in order to become the local libahunt, the werewolf that can fly into the storm clouds and drive away the most terrible storms that would otherwise destroy the crops and drive the village to starvation. Even in 1880s, the industrial revolution was only beginning to seep into rural Estonia and the other Baltic States (Latvia, Lithuania). Alexei’s grandfather warns him not to use the magic too often or for his own advantage or he will lose control of the shapeshifting ability. There is a series of terrible storms one winter and Alexei has to use the wolf pelt time after time after time to protect the village. In the spring, the earthly wolves are hungry and starving as well. They begin to attack the farmers in the fields, including Alexei. Alexei loses control of the shapeshifting and becomes a killer, just like the starving wolves in the forest. He runs away from his home, through Latvia and Lithuania as well as Poland, seeking someone who might still enough of the old magical practices to save him from the killer he has become.

You have an interesting background. Tell us a little about how your education and past experiences prepared you for this book.

I studied medieval history at Yale and then Eastern Orthodox history and theology at St. Vladimir’s Theological Academy. I served as parish priest for a small Eastern Orthodox congregation at Columbia University for many years. I celebrated services, preached sermons, performed marriages and funerals. I counseled the confused and the despairing, taught those with questions, rejoiced with the joyful. I read. I shared what I had discovered on my own journey. Most importantly, I listened. Most people already knew the answers to their own questions; they just needed someone to help them listen to themselves.

Hopefully, that listening and sharing is reflected in my writing. I listen to the characters and help them to discover who they are and what journeys they are on. I share aspects of myself with each of them and they share themselves with me; if I am quiet and listen, I can share not only their joys and frustrations and despair myself but communicate their experience to my readers.

Priesthood is primarily a way of being, of bridge-building. In writing, I try to be my truest self and attempt to build bridges between cultures and histories, practices and experiences, characters and readers.

You’ve mentioned Jim Butcher and others as influences. How has it helped to explore other authors who channel myth and folklore in fresh ways?

In the Dresden Files series, Jim Butcher uses Celtic folklore in amazing ways; the Felix Castor novels by Mike Carey adapt beliefs about ghosts and zombies and shapeshifters in intriguing and unexpected ways. Kate Griffin paints stunning word pictures in her Midnight Mayor and Magicals Anonymous novels, and uses urban legends and beliefs to bring magic to life. I think these authors show us how the old—and the new!—can still open doors into other worlds and help us see our world as still drenched with magic. I can appreciate both science and magic: just because we can explain something today—like conception—does not make it any less magical.

*****

Stephen Morris has degrees in medieval history and theology from Yale and St. Vladmir’s Orthodox Theological Academy. A former priest, he served as the Eastern Orthodox chaplain at Columbia University. His previous academic writing has dealt primarily with Late Antiquity and Byzantine church life.

Stephen Morris has degrees in medieval history and theology from Yale and St. Vladmir’s Orthodox Theological Academy. A former priest, he served as the Eastern Orthodox chaplain at Columbia University. His previous academic writing has dealt primarily with Late Antiquity and Byzantine church life.

He is also the Chair of the CORE Executive of Inter-disciplinary.net and organizes annual conferences on aspects of the supernatural, evil and wickedness, and related subjects.

Stephen, a Seattle native, is now a long-time New York resident and currently lives in Manhattan with his partner, Elliot.

To learn more about Stephen, please visit his website.

- Cthulhu Blues by Douglas Wynne - November 30, 2017

- Down to No Good by Earl Javorsky - November 30, 2017

- Storm Wolf by Stephen Morris - October 31, 2016