First Blood Turns Forty: Rambo’s Father Reflects on His Iconic Creation by Hank Wagner

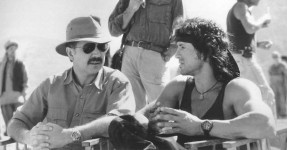

Although it might be hard to believe, forty years have passed since David Morrell’s classic thriller FIRST BLOOD was first published. During that time, the book’s protagonist, Rambo, has become well known across the globe, primarily due to four movies starring Sylvester Stallone. We thought it appropriate to celebrate this milestone anniversary by sitting down with Morrell, the author who started it all with his creation of the traumatized ex-soldier, to get his perspective on the novel and its important literary and cinematic legacy.

This is the 40th anniversary of the publication of FIRST BLOOD. For the occasion, you revised your novelizations for the second and third Rambo films and then wrote introductions for them. You also wrote an e-essay, “Rambo and Me: The Story behind the Story.” What was it like, revisiting those works?

Four decades. Amazing. As I revisited FIRST BLOOD and the novelizations I wrote for Rambo (FIRST BLOOD Part II) and Rambo III, I was surprised by how little the world had changed since 1972. The United States is as polarized today as when FIRST BLOOD was published. The term “post-trauma stress disorder” didn’t exist back then. Nonetheless that’s one of the themes of my novel, and now after Afghanistan and Iraq, two wars that lasted even longer than Vietnam, PTSD is more prevalent, a daily item in the news. In Rambo III, the character went to Afghanistan. The day the movie opened, the Soviets retreated, probably because they knew Rambo was coming. That was the end of that. Or so it seemed, and yet two decades later, Afghanistan is as much in the news as ever.

Anything you would change about FIRST BLOOD, given the chance?

For the e-book, I made slight changes. Nothing major. But I’m a compulsive reviser, and as I checked the electronic file for digital glitches, I couldn’t help tinkering. Certainly nothing major like the way I revised TESTAMENT and LAST REVEILLE for e-books. The changes to those books were so huge that I needed to get new copyrights.

Do you still have the original notes and/or manuscripts for FIRST BLOOD? Are they part of the papers you donated to University of Iowa?

I have a carbon copy of the manuscript for FIRST BLOOD and a binder of notes that I made when I wrote the novel. None of that was donated, In fact, I have a box of notes, correspondence, and edited manuscript for every book I wrote. Sometimes I need information from them. A while ago, I had a conversation with a friend who’s a best-selling author, and he told me that he throws everything out when a project is finished. I’m not sure that’s a good idea. I have an archival mentality. I keep everything, just in case.

I have a carbon copy of the manuscript for FIRST BLOOD and a binder of notes that I made when I wrote the novel. None of that was donated, In fact, I have a box of notes, correspondence, and edited manuscript for every book I wrote. Sometimes I need information from them. A while ago, I had a conversation with a friend who’s a best-selling author, and he told me that he throws everything out when a project is finished. I’m not sure that’s a good idea. I have an archival mentality. I keep everything, just in case.

Can you describe the time frame in which you wrote the book, from idea to final text?

I began FIRST BLOOD in the summer of 1968 when I was at graduate student at Penn State. A science-fiction writer from the Golden Age of the 1950s, Philip Klass whose pen name was William Tenn, agreed to give me private lessons about writing, and critiqued the manuscript every hundred pages or so. I worked on it for a year and then interrupted it to write my dissertation on John Barth so that I could graduate and get a teaching job. I returned to FIRST BLOOD in the spring on 1970 and continued after I went to teach at the University of Iowa. I finished it in the early summer of 1971. It was published in May of 1972. Subtracting the dissertation, I spent three years on the novel.

When did you start to get an inkling that the book was going to be successful? Or that is might become a classic? Did you ever think it would still be discussed forty years later?

In the 1972 world of publishing, FIRST BLOOD was very different. Except in pulp fiction, there had never been a novel with that much action and violence. I wrote my Master’s thesis on Hemingway’s style, and I was fascinated that Hemingway could write about action so often and avoid all the clichés that we associate with pulp writing, like “A shot rang out.” So I spent a long time studying how he did it. My goal was to write an action book that didn’t feel like a genre book. But I wondered if a publisher would take the risk. It’s a very intense book. My first sense that the book might last came when every major newspaper and magazine reviewed it enthusiastically, except for TIME magazine, which I’ll get to. Almost immediately there was a big paperback sale (in those days hardback publishers signed subsidiary contracts with paperback publishers). The Literary Guild picked it up. Columbia Pictures bought the film rights. Teachers began using the text in high schools and universities. When Stephen King taught creative writing at the University of Maine, FIRST BLOOD was one of only two texts he used. The book was translated into twenty-six languages. First novels don’t usually get that kind of attention. And the films were yet to come.

In the 1972 world of publishing, FIRST BLOOD was very different. Except in pulp fiction, there had never been a novel with that much action and violence. I wrote my Master’s thesis on Hemingway’s style, and I was fascinated that Hemingway could write about action so often and avoid all the clichés that we associate with pulp writing, like “A shot rang out.” So I spent a long time studying how he did it. My goal was to write an action book that didn’t feel like a genre book. But I wondered if a publisher would take the risk. It’s a very intense book. My first sense that the book might last came when every major newspaper and magazine reviewed it enthusiastically, except for TIME magazine, which I’ll get to. Almost immediately there was a big paperback sale (in those days hardback publishers signed subsidiary contracts with paperback publishers). The Literary Guild picked it up. Columbia Pictures bought the film rights. Teachers began using the text in high schools and universities. When Stephen King taught creative writing at the University of Maine, FIRST BLOOD was one of only two texts he used. The book was translated into twenty-six languages. First novels don’t usually get that kind of attention. And the films were yet to come.

How does it feel that people still come up to you at conventions to talk about it? Also, how does it feel to have influenced so many of the current crop of thriller writers, many of whom would actually acknowledge that influence?

People who know me understand that at heart I’m a teacher. I’m at my happiest when I provide information that might help someone. If FIRST BLOOD helped other authors find their own way, that’s terrific. There have now been two generations of thriller authors since FIRST BLOOD, and I suspect that many of the second- generation authors no longer realize how the techniques I experimented with in FIRST BLOOD entered the mainstream of thriller writing.

What about context for FIRST BLOOD, described in one review as “carnography.” Was violence in the air? I’m thinking about films that came out in 1972, like DELIVERANCE, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, THE GODFATHER, DIRTY HARRY, and the like. Also, 1972 was a milestone in terrorism, what with the strike at the Olympic Village in Munich. What literary precedents informed the book?

Ah, now we get back to TIME magazine, the only negative major review. TIME hated FIRST BLOOD. The reviewer thought the novel was immoral and called it “carnography,” a meat novel, the violent equivalent of pornography. The reviewer must’ve been having a bad day. He sensed what FIRST BLOOD was going to do to thriller writing, that the stakes would be higher and more extreme from now on. This made the reviewer feel threatened. Far from taking offense, I was gladdened. Somebody was actually paying attention. Someone understood the radical change I’d attempted.

Ah, now we get back to TIME magazine, the only negative major review. TIME hated FIRST BLOOD. The reviewer thought the novel was immoral and called it “carnography,” a meat novel, the violent equivalent of pornography. The reviewer must’ve been having a bad day. He sensed what FIRST BLOOD was going to do to thriller writing, that the stakes would be higher and more extreme from now on. This made the reviewer feel threatened. Far from taking offense, I was gladdened. Somebody was actually paying attention. Someone understood the radical change I’d attempted.

Had you read DELIVERANCE (1970) before embarking on FIRST BLOOD? Those two books appear to have some of the same DNA, at least on the surface. If not, did you read it subsequently and feel any kinship with Dickey?

I indeed read 1970’s DELIVERANCE, which was published mid-way through the manuscript of FIRST BLOOD. I was impressed by its realistic approach to action, although there wasn’t much action proportionally in the book, and it didn’t influence me. I think James Dickey made a wrong choice with the first-person viewpoint. In the final pages, the main characters need to escape the suspicion of a lawman who can’t ever know that they killed men who might be his relatives. This is emphasized again and again. No one can ever know what happened in those mountains. But the novel is written in the first-person and only a couple of million of us know the secret. The novel could as easily have been written in the third-person, avoiding this logical inconsistency. The thriller writer who most influenced me was Geoffrey Household, whose ROGUE MALE is a masterpiece of outdoor action, and when I read DELIVERANCE I felt that same kinship. When people go into the forest and the mountains, powerful things can happen.

Did you make a conscious decision to up the ante re: violent content in the novel?

Household’s specialty was understated outdoor action, in ROGUE MALE and WATCHER IN THE SHADOWS, for example. I wondered what would happen if I raised the stakes and applied a much greater vividness than Household ever attempted. It’s probably significant that Sam Peckinpah’s THE WILD BUNCH was released in 1969 when I was writing FIRST BLOOD. I wasn’t imitating Peckinpah. I didn’t change my approach because of the film, but I did sense that I was doing something that was new and could change the way people thought about thrillers. When I asked Household for a publicity quote, he declined, saying that my novel was far too bloody. The title would have been a clue. Household understood, even though he didn’t like it, that I was taking what I’d learned from him and raising it to a new level.

Household’s specialty was understated outdoor action, in ROGUE MALE and WATCHER IN THE SHADOWS, for example. I wondered what would happen if I raised the stakes and applied a much greater vividness than Household ever attempted. It’s probably significant that Sam Peckinpah’s THE WILD BUNCH was released in 1969 when I was writing FIRST BLOOD. I wasn’t imitating Peckinpah. I didn’t change my approach because of the film, but I did sense that I was doing something that was new and could change the way people thought about thrillers. When I asked Household for a publicity quote, he declined, saying that my novel was far too bloody. The title would have been a clue. Household understood, even though he didn’t like it, that I was taking what I’d learned from him and raising it to a new level.

Are we making the same mistakes with our vets returning from Iraq and Afghanistan that we made with those returning from Vietnam?

Having lived through the Vietnam years, I can verify the reports that returning Vietnam veterans were spat upon by war protestors and called baby killers. Many people couldn’t grasp the idea that the military doesn’t start wars. Politicians do. The military pledges itself to defend the United States. If politicians declare war, the military isn’t allowed to object. It’s an instrument of policy. It doesn’t make that policy. Because of FIRST BLOOD and Rambo, some people finally understood that distinction. I don’t know of any instance in which those who protested against our involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrated their anger against returning war veterans. If anything, the sacrifice of the veterans is now honored, even as protestors condemn the policies that sent those soldiers to war.

Coming here from Canada, did you ever take any flak for writing about social problems unique to America?

I’m now an American citizen. Back then, my foreign status helped me write the book. I was very conscious of not being a citizen and not having the right to offer political opinions. So when I wrote FIRST BLOOD, I didn’t include any windy political speeches about the Vietnam War. I just let the plot and the action speak for itself. As a result, the book reads the same now as it did in 1972. Nothing in it has dated because it isn’t specific to 1972. From this, I learned to take a long view when I’m writing. I don’t use current slang, and I always ask myself what a passage will read like in thirty years in terms of cultural and political references that can become incomprehensible very quickly.

I’m now an American citizen. Back then, my foreign status helped me write the book. I was very conscious of not being a citizen and not having the right to offer political opinions. So when I wrote FIRST BLOOD, I didn’t include any windy political speeches about the Vietnam War. I just let the plot and the action speak for itself. As a result, the book reads the same now as it did in 1972. Nothing in it has dated because it isn’t specific to 1972. From this, I learned to take a long view when I’m writing. I don’t use current slang, and I always ask myself what a passage will read like in thirty years in terms of cultural and political references that can become incomprehensible very quickly.

Can you talk a little bit about the phenomena of Rambo? Is it humbling to think you’ve created a character with the name recognition, of, say Sherlock Holmes, Superman and the like?

It’s amazing and humbling to have created a character who achieved worldwide recognition along with thriller icons like Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, James Bond, and Harry Potter. Even if people haven’t read my work, they‘ve heard of Rambo in every country in the world. His name was on the Berlin wall after the USSR collapsed. A Polish journalist told me that, during the Solidarity demonstrations that brought down the Soviet Union, Polish demonstrators watched illegally imported Rambo films, then dressed up like him, and went out to challenge the soldiers. The Polish journalist told me that, in an indirect way, Rambo ended the USSR. That’s why I used the word “humbling.” To have created a character that influenced world history, even in an indirect way, is rare. Astrophysicists even use Rambo’s name to describe a cluster of dense stars. All that makes me smile. Sometimes I hear someone refer to Rambo in a news program or on a sports show or in conversation, and the character is so much a part of the culture that it takes me a moment to remember that I created him. That makes me smile also.

- THE GOD IN THE SEA with Paul Kemprecos - April 4, 2024

- FOR WORSE with L. K. Bowen - April 4, 2024

- HIT AND RUN with Vincent Zandri - April 4, 2024