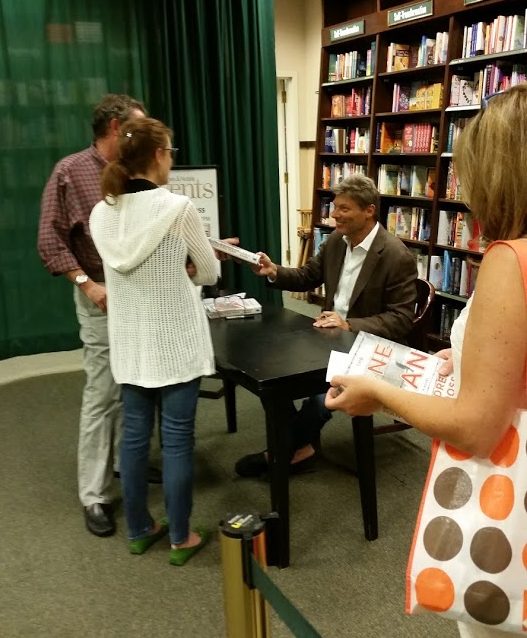

Between the Lines: Interview with Andrew Gross

A Thriller of Heartbreaking Realism

By Josie Brown

By Josie Brown

Real thrillers are a part of everyday life. Proof of this is Andrew Gross’s personal connection with concentration camp survivors, which inspired the creation of his latest novel, THE ONE MAN.

Critics are already praising this sixth novel from the New York Times bestselling author as his finest book to date, and for good reason. It’s a page-turner that embodies the heartbreaking realism of one of recorded history’s most appalling crimes against humanity.

Here, the novelist shares with The Big Thrill his process for creating a story filled in equal parts with sorrow, despair, courage, and hope:

The Holocaust and World War II are sensitive topics for many of its survivors. In fact, you mention in your author’s note that your own father and father-in-law have never spoken of their losses—yet, at the same time, their experiences were the catalyst for the book’s concept. How did this come about?

My father-in-law came to this country from Warsaw in April, 1939, six months before the war. His family stayed, and of, course, became swallowed up in the fate of most Jews left in Poland. He never learned the fates of any of them. In the end, he was the only one in his family to survive the war.

Like a lot of survivors, he went through life with a cloud of sadness over him, a mantle of guilt and loss. In 1941, when the U.S. entered the war, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and because of his facility with languages, was placed in the OSS. He never spoke, even to his own children, of those experiences either.

In writing THE ONE MAN I wanted to delve into what was behind that sadness and shame that my father-in-law clearly carried for the rest of his life. I knew there was something he had buried very deeply, that he wouldn’t let surface. So the idea of atoning for the guilt of surviving became something I embraced and gave life to. In many ways, the true character of the book is the old man in current times at the beginning and the end of the book who finally let’s go to his daughter and tells his story. In many ways, I wanted to write the story I thought he, my father-in-law, would write.

The backstory of THE ONE MAN starts with a great escape—from the Polish concentration camp, Auschwitz. One of your protagonists, Nathan Blum, is charged with a very serious mission: exfiltration of a nuclear physicist, Alfred Mendl. To do so, Blum, must break into Auschwitz. Had such an infiltration ever been done before?

Well yes, in a way. It was actually my agent, who wrote his college thesis on Holocaust literature, who challenged me to find any historical precedents for what took place in my own story for his own marketing of the book. And in doing so I came across the story of Dennis Avey, a British POW, kept at a camp near Auschwitz, who actually exchanged uniforms with an Auschwitz prisoner on a work detail and spent a day and a night inside the death camp. His motive was curiosity and horror at the condition of the underfed prisoners who showed such little will to survive. So what Nathan has to do in the book had already been done. My paths in and out are quite different, though I always wondered how Avey’s life would have ended up if his prisoner counterpart never came back the next day to re-exchange uniforms.

Whether within or outside Auschwitz, practically every scene in THE ONE MAN has hair-raising twists and turns. Are they the work of your active imagination as it channeled the countryside of Poland during the WWII, or are they based on true stories of heroism and escape, or a bit of both?

Some of both. The story of the poor baker who has a gun misfire at the back of his head—three times—was told to me by Morris Pilberg, a grandfather of my daughter’s boyfriend, and an Auschwitz survivor. It actually happened to him. Interestingly, I watched Schindler’s List again midway through writing the book and saw the same scene. It horrified me—had I unwittingly stolen it from there? I said to my wife, didn’t Morris tell us the same tale? Until I saw that Spielberg had used survivor’s Shoah accounts of their captivity and Morris had made such a testimony, so maybe Spielberg and I took it from the same source! The woman on the way to the gas who refuses to go was another first- hand account told to me by the mother of a close friend.

Of course, I read through several first-hand accounts of life there, so much of the perspective of the place in the book comes through their accounts, including the underground economy there, including the bribing of guards, which plays an important part in the book. While yes, much of what takes place there came from me, as a Jew, writing about the Holocaust, one can never, never stray very far from the truth, and I didn’t.

The function of memory is integral to the plot, especially as it pertains to the salvation of another protagonist, Leo Wolciek. Was it research that inspired your use of memory as a device? Or did it arise from creative inspiration, and your research on the topic validated your use?

I think they work hand in hand—not only my memory, but the imagined memory of my old man who starts the story out and concludes it, confessing to his daughter the source of the grief that has governed his life. In saying that, though, I feel compelled to say that I think the book ends on a triumphant note, and though I wanted to be truthful and accurate in what took place there, I never set out to write a book about atrocity—but heroism. And hopefully it is the courage and perseverance of Nathan Blum that lights up this story and makes it different from the rest.

The game of chess plays a very important role in the book. Where did you get the idea of using it as the plot device that, as I see, is a turning point of the book? And, through your research, did you find that such friendships between prisoners and those who ran the camps had taken place?

I dunno, is the best answer I can give. I guess it just came to me. I may have read in an account how people played chess with makeshift pieces of wax and wood and then, without giving too much away, in needing to find someone with the kind of mind who could absorb all Alfred’s atomic theories, who better than a young chess prodigy a brilliant mind?

As with most historic subjects, your research for this book was extensive. What was your process for delineating the history of nuclear fission?

I have to admit, I’m a guy who barely muddled his way through eighth grade Earth Science. To me, the challenge of including the atomic science was to show with clarity what Alfred Mendl knew that the Allies needed so urgently, at the same time presenting it in a way that anyone could understand, and more importantly, that wouldn’t bore them to death. So I set up this dialogue between Leo and Alfred, the cocky student with the astonishing brain and the patient, fatherly instructor who knows he has potentially found the one way to get his proprietary knowledge out. It was a challenge, but I’m told the “science” fits seamlessly into the book.

Some of your plot points include blunders made because, even during wartime, people are human. How the exfiltration plot is discovered is one example (truffles); another is a momentous decision Nathan makes toward the end of the book, causing fatal consequences. In your research, did you run across other human blunders that caused you to think, “Wow! Talk about a twist of fate…” Or better yet, “This is something I can use in my plot…”?

Well, I don’t think of them so much as blunders. Martin Franke, the German Abwehr colonel, is a person of keen intelligence and an even stronger passion to restore his standing who puts together the pieces of a puzzle. Coded messages were routinely transmitted into occupied zones.

Nathan, as you say, makes a momentous decision that yes, jeopardizes the mission but seizes the moral high ground. I wonder how many would call it a blunder, and how many would hail it for its courage and affirmation.

All my books use the theme of randomness, how just a tiny shift in action can make a huge shift in the arc of a character’s fortune and fate. The way I see it, humanity is as important as all the planning and preparation that goes into this mission, and in the end, humanity wins out.

I’m sure you get a lot of questions about your collaboration with James Patterson. As it pertains to the trajectory of your career, what has been the upside? Have you seen a downside to it?

I’m long out of my association with Jim, other than bumping into him now and then in Florida. I will say that I was lucky that as his first ongoing co-writer I was able to platform that role into a fairly successful career. When I came into doing my own books, I was treated by my publisher as a writer with bestseller status, and thereby bypassed some of the steps and hurdles most other writers had to traverse.

My first book, The Blue Zone, went solidly on the bestseller lists and was sold to 20 countries. That said, the association still follows me, and it has had a qualifying effect on my career as well.

Jim is known for a certain style of book (which proves to be staggeringly successful) and you are inevitably associated with the same style, no matter how your work evolves. It’ll be a good test to see if THE ONE MAN finally allows me to finally put that behind me a bit.

What project is next on the horizon for you?

I’m staying in the same vein. I want to write stories based on historical fact that I can take in a different way. I’ve already finished the next novel, based on British and Norwegian raids to put an end to the Nazi efforts to create an atomic bomb. It’s kind of an old fashioned Alastair McClean WWII adventure called The Saboteur— one person’s staggeringly courageous act (which has never received much attention) that may have singlehandedly altered the war.

- Up Close: Jane Smiley - November 30, 2022

- Up Close: Lisa Barr - February 28, 2022

- Up Close: Kaira Rouda - December 31, 2021