Special to The Big Thrill: Screenplay vs. Novel Writing by Terry Hayes

Not long after I had first moved to Hollywood, I ended up in a meeting with several senior studio executives on the 20th Century Fox lot. The subject we were dealing with was a remake of PLANET OF THE APES, the classic 1968 movie starring Charlton Heston as an astronaut and the great Roddy McDowell as a chimpanzee.

Oliver Stone was a producer – and being courted assiduously by Fox to also be the director – and Don Murphy, who some years later would be hugely instrumental in bringing the Transformer movies to the screen, was the other producer. My role was to write the script – an assignment which had come my way thanks to my writing work on, among other things, two of the Mad Max movies and DEAD CALM, which had launched Nicole Kidman’s international career.

The Apes project was no easy task – for a start, the screenplay of the original had been adapted from a novel by the legendary Rod Serling, the former paratrooper who created the TV series THE TWILIGHT ZONE. Not only that, the ’68 version is widely regarded as a classic movie with what is, in many people’s opinion – mine included – one of the greatest movie endings of all time. Not intimidated by such an illustrious pedigree – you should understand, I was very young then – I had set to work and written a first draft of the proposed reboot. It was that 120-odd pages which were under discussion in

the expansive executive office on the lot – how to improve it, how to sharpen it, how to get it one step closer to that ever-elusive target called a greenlight.

In the midst of endless talk about character arcs, second act climaxes and various ideas to match that remarkable ending, the senior Fox executive in the room – who had been looking increasingly distracted and preoccupied – suddenly interrupted and said: “You know what we need?”

Everyone shook their heads.

“A baseball game.”

I’m sure the rest of us were all thinking the same thing – a what? Finally somebody asked him what he meant. “I think it’d be really cool,” he replied, “to see the apes and humans playing baseball.”

To say that this had absolutely nothing to do with the novel, the original movie or any of the story, ideas and thoughts under discussion – well, let’s just say that would be a massive understatement.

“The two sides are sort of at war – why would the apes and humans do that?” I asked. For those who don’t remember the original movie, it was a very violent and confronting piece of work – the humans were a lesser life form, they were hunted for sport, used as slaves or were subjected to a range of medical experiments. In short, the whole story was a role reversal – one where the humans were fighting for freedom and their very lives.

Baseball is a fine sport but there didn’t seem much time in a story dealing with such huge issues and desperate stakes to stop and have a ballgame, cool or otherwise.

Somebody – it was probably Don, but it was a long time ago and I can’t be sure – said there seemed to be a host of problems with it, but did the executive have any idea of how it could be made to work?

“That’s not my job,” the executive said, “that’s up to you guys to figure out.”

So it started – a long and rambling argument with each side digging in a little deeper as the minutes turned to an hour. Finally, I said: “Look, I’m sorry – but I just can’t see any way a baseball game is ever going to make it into the story. Okay?” There was silence on the other side of the desk.

As a sort of joke, to lighten the mood, I added: “Anyway, what would I know about baseball – I mean, I’m Australian.”

The senior executive didn’t smile. “That’s true,” he said. “And maybe that’s the problem.”

I figured, from then on, that my days with the apes were pretty well numbered and so it turned out – not just for me, but for all of us on our side of the desk. Within a year, the studio executives had also been 86’d. Fox, though, did go on to make the movie – over a decade later with Tim Burton taking the director’s chair. Whether he and the writers had to contend with somebody advocating – let’s just say – an ice dancing sequence, I have no idea. Maybe they did – it is Hollywood, after all.

The reason for recounting this experience is to illustrate what I believe is one of the major differences between writing a novel and writing a screenplay – when you’re writing a novel, you don’t have to deal with fools. Well, one maybe – yourself – but that’s all.

Okay, so the Apes story is an extreme example of the problem and there are plenty of intelligent and thoughtful people working at the studios or making movies – but the essential fact remains the same. In most cases, writing novels is playing singles; writing movies today is pretty much a team sport.

The on-screen credits reflect this – how often is the screenplay attributed to a single writer, especially if it is a major summer release? Hardly ever. In addition, there are “story by” credits, “additional dialogue” credits, “from an original idea” credits and on and on. The fact is (there are exceptions, of course), that on big studio projects writers come and go – it seems like a select group of people are constantly rewriting each other and this development process can go on for years; writers frequently work in teams of two or three; often, when a script is on the so-called ‘fast-track’, two teams work independently; people are brought in to punch-up the dialogue; and specialists are sometimes hired to craft action set-pieces.

Then there is the director, the producers, the studio executives (see baseball game, above), and the movie stars. Everybody has an input, everyone has an opinion, everyone wants their voice heard. Years ago, a writer would be involved in a script meeting, then it became a script conference, and pretty soon – I’m sure – it will be a script convention. They’ll hold ’em in Vegas, that’s how many people will be involved.

POCAHONTAS, the Disney animated movie, is a good example. Twenty-eight people received writing credits. Twenty-eight! For a very short – 81-minute – movie. What did they all do? In addition, of course, there were two directors, a producer and Team Disney.

Under such circumstances, it is very difficult to work out how much of one individual’s ideas and writing actually survives in the finished work. Authorial vision is neither much valued, not usually achieved, in a Hollywood where the number of movies being made is rapidly becoming smaller but the financial bets are becoming astronomically larger.

I think, especially as they get older, this situation starts to weigh heavily on a lot of writers – if not on their souls, at least on their minds. They like to think that it is their writing, their story, which has ended up on the screen. As Raymond Chandler, the great author of hard-boiled novels and who was also nominated twice for an Oscar as a screenwriter, once said about working in the movies:

“I am a writer, and there comes a time when that which I write has to belong to me, has to be written alone and in silence, with no one looking over my shoulder, no one telling me a better way to write it. It doesn’t have to be great writing, it doesn’t even have to be terribly good. It just has to be mine.”

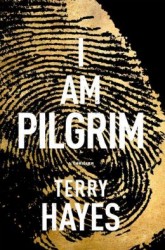

Having now, like him, worked in both mediums – my novel I AM PILGRIM – is about to be published in the United States – I know exactly what he meant. I look at the cover of my book, pinned to the wall above the desk, and I know, for better or for worse, in sickness and in health, I did that.

Don’t get me wrong – I really enjoy the highly-disciplined task of writing movies and if the film rights to Pilgrim should be fortunate enough to be sold, I will have no hesitation in signing-on to do the script. I would, however, know exactly what I was getting in to. For as long as it took, I would no longer be playing singles; I would be part of a quite large and unwieldy team – one which, both practically and creatively, would be led by the director.

That’s the way it is in Hollywood, but I do know one thing – no matter the cost, just as a matter of pride, there won’t be any simians-versus-humans baseball game.

*****

Terry Hayes is the award-winning writer and producer of numerous movies. His credits include PAYBACK, ROAD WARRIOR, and DEAD CALM (featuring Nicole Kidman). He lives in Switzerland with his wife, Kristen, and their four children.

Terry Hayes is the award-winning writer and producer of numerous movies. His credits include PAYBACK, ROAD WARRIOR, and DEAD CALM (featuring Nicole Kidman). He lives in Switzerland with his wife, Kristen, and their four children.

- THE GOD IN THE SEA with Paul Kemprecos - April 4, 2024

- FOR WORSE with L. K. Bowen - April 4, 2024

- HIT AND RUN with Vincent Zandri - April 4, 2024